Posted 2020-09-08

I’ve had a lot of questions lately about my online teaching methods lately, so I thought I’d share my rationale behind them. The course I’m currently teaching, Introduction to Computational Literary Analysis, in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, has a unique technological stack:

- A course website. It’s built using Haskell and the static site generator Rib, and styled with Tufte.css, the CSS framework based on design concepts from Edward Tufte

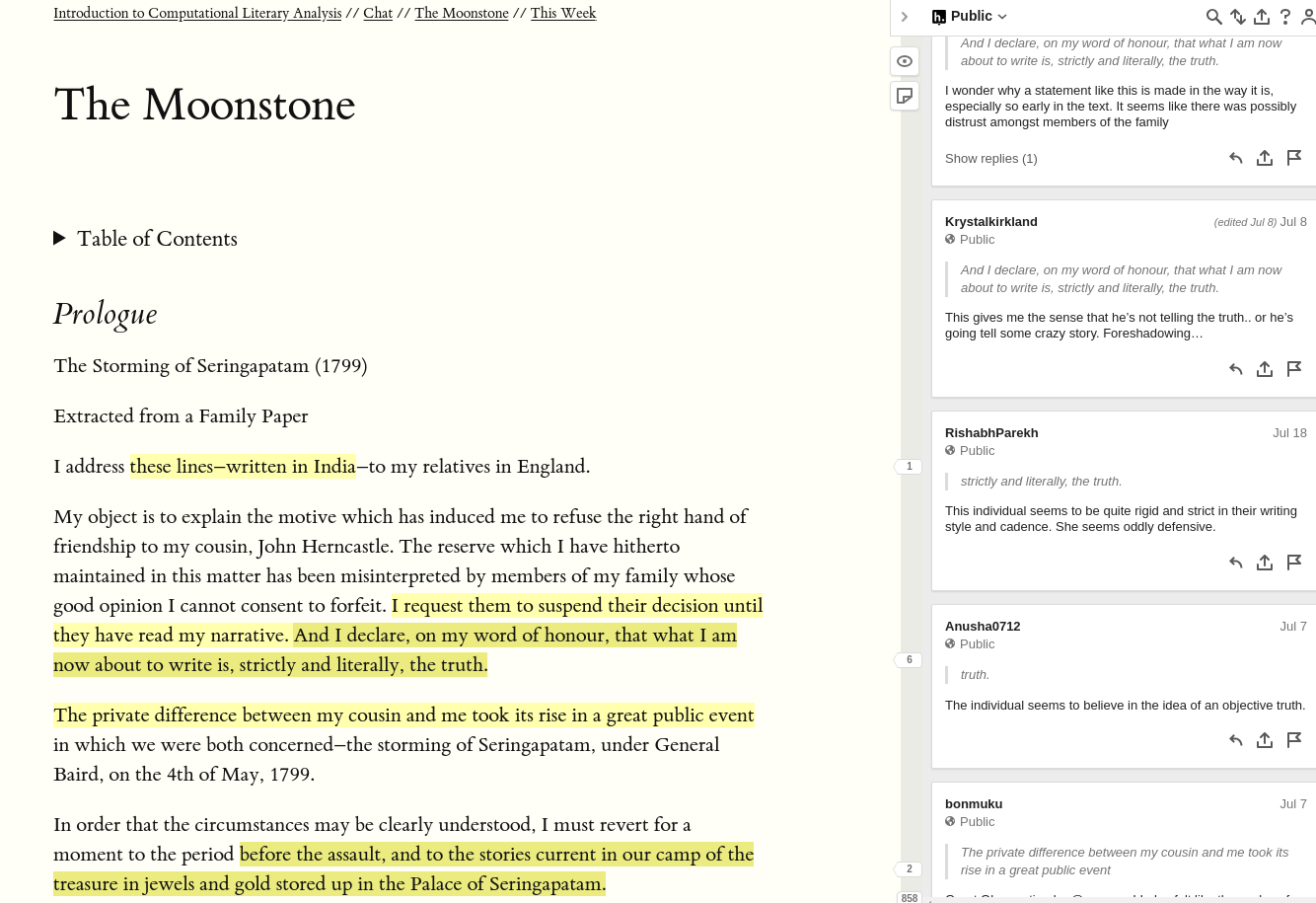

- A course readings platform made with Hypothes.is, open-source web annotation software

- A course communications system made with Zulip, the open-source, threaded, text-based chat platform

Why use Hypothesis?

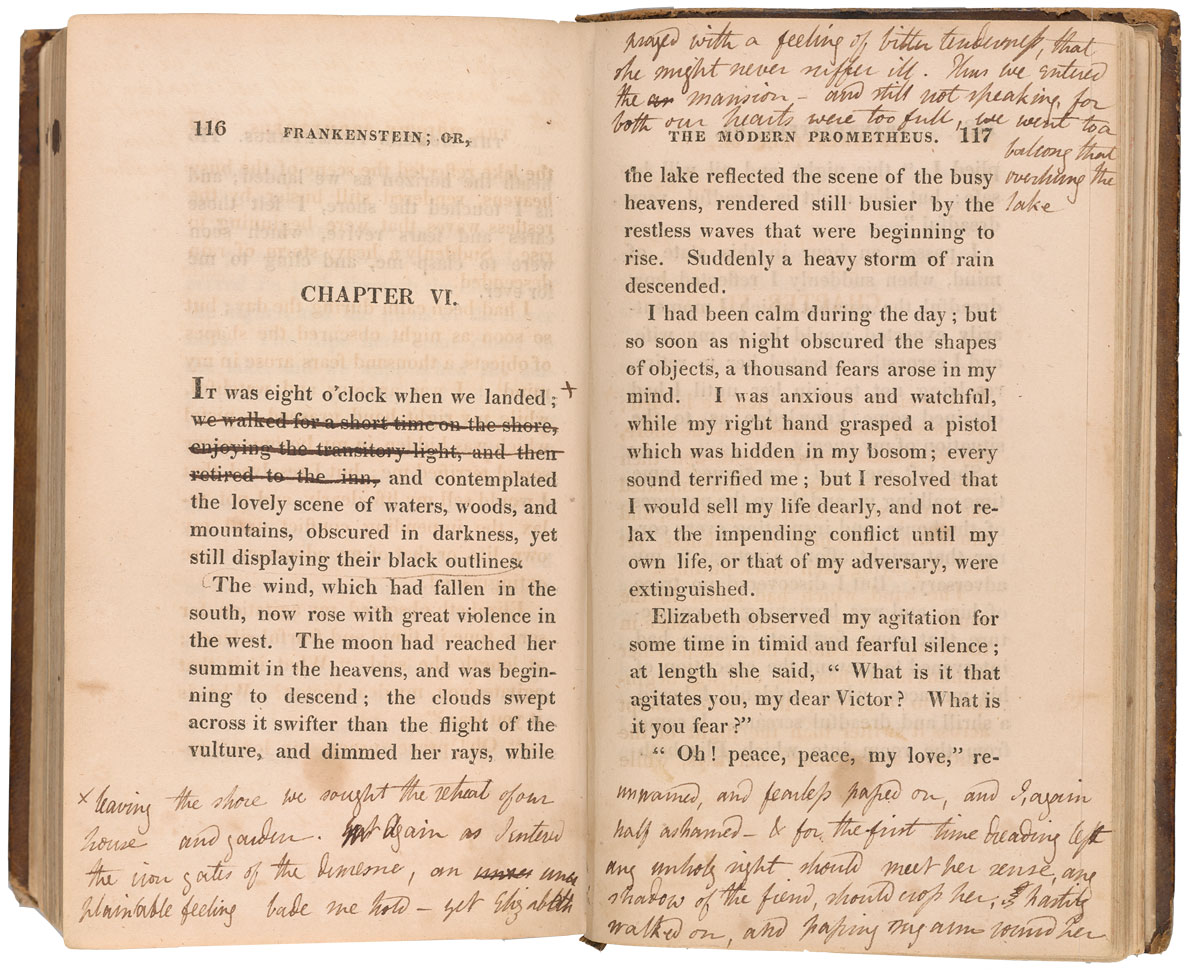

As literary scholars, we talk about texts. We are often engaged in what one might call marginalia: writing, about another text, with reference to a very specific, page- or line-level passage of that text. Very rarely does this kind of writing actually take place in the margins of books, any more, but it recalls a time when conversations would happen in the margins. In the days when books were expensive, luxury items that were passed around among a coterie of friends, this would happen more often. But as books became cheaper, and were loaned around less frequently, conversational annotation became more of a rarity. Furthermore, the recent shift to digital textual media made this even harder: without electronic margins, and electronic pens to write in them, we have had difficulty recreating the experience of social annotation. Our writing has become increasingly divorced from the writing it discusses, and it has become less social, and more solitary.

This is where Web 2.0 technology comes in. Whereas Web 1.0 was static—you could read pages but not interact with them—Web 2.0 was dynamic: website visitors could interact with the pages, changing their content. Virtual “bulletin boards,” as the old metaphor went, became possible, and with them, virtual margins.

Hypothes.is is an open-source web annotation platform, designed to do just this. It allows for highlighting, commenting, and discussing a text, in the margins of the text itself. It is already in wide use for annotating news articles, scientific journal articles, and more, but its ideal use case, in my opinion, is for literary texts.

Why Zulip?

Again, as literary scholars, teaching in literature classrooms, we talk about text. It only makes sense that we do that using text. Zulip is an open-source text-based chat service, akin to services like Slack, but open-source, and with a few added features, like threading. Threading allows for a non-linear, asynchronous way of sorting discussions by topic. It allows you to join a past discussion that has since moved on to a new topic, and to change the topic without derailing a previous conversation. This does the work, technologically, of a intructor/facilitator, whose labor consists so much of discussion moderating. “Let’s go back to that earlier point,” and “let’s not forget X” are common refrains in a classroom that shoehorns the multiple timelines of students’ thoughts into one linear narrative.

Why not just use Zoom?

Too often, we accept technological services as the necessary background of our lives, without considering their social and economic consequences. We want them to just work, and get out of the way, so that we can do our jobs. However, for literary critics, that is highly paradoxical–and hypocritical, even—since we are so conscious of the social implications of other phenomena. This is to say, if we write an article about latent colonial ideologies in Jane Austen’s Persuasion, but we do it in Microsoft Word, on a laptop running MacOS, which we bought on Amazon, there are economic implications for what we are doing, materially, that are analagous to what we criticize in our article. We’ve voted with our dollars in favor of giant corporations, to the detriment of community-based alternatives.

Economics aside, there are serious ethical issues behind using proprietary software instead of open-source software. To borrow an analogy from switching.software, using proprietary software is like eating a slice of cake at a diner: we can’t be sure what the ingredients really are, and we just have to trust that it’s going to be what we expect. Using open-source software, however, is more like eating a piece of homemade cake: we know the recipe, we trust the ingredients, and we can reproduce it ourselves, if we want. We can even modify the recipe to our liking, and make it better.

Now, we can’t make conscious choices for everything in our lives. That would be exhausting. But some choices are easy to make, and software choices are among those. After the pandemic hit, we all swarmed to Zoom without stopping to consider whether it’s a good idea. Our universities and libraries gave the for-profit Zoom corporation millions of dollars, and its stock price skyrocketed. Meanwhile, we have largely ignored the endless stream of articles that have reported on Zoom-related security problems, the cultural phenomenon of “Zoombombing,” and more.

In my course, I largely replace videoconferencing with text-based conferencing on Zulip. But for the times when we want to meet using video, I use Jitsi, an open-source alternative that’s simpler, nicer, and more ethical.

Why host videos on PeerTube?

University-based video hosting, like ours at Columbia, locks course videos behind a firewall, where they can only be accessed by other students within the university. This seems like it would be bad for the future life of the lectures: if students leave the university, for instance, and want to revisit the course material, they might no longer have access. The big video hosts, like YouTube, are even worse for course materials, since they’re ad-based. I won’t have my students watch ads just to get to my course material. So I opted to post my videos to us.tv, a PeerTube instance. PeerTube is an ad-free, open-source, decentralized video hosting federation, where instances that follow one another share videos between them, using a Bittorrent-like protocol. My lecture videos are thus accessible across a wide variety of servers. This is important when we consider the potential that students might be calling in from countries with censored or restricted Internet: if one server has been blocked, the videos are still accessible on others that follow it.