Posted 2018-03-07

What is a chapter, really? Inspired by Nicholas Dames’s work on the history of the chapter (some of which appeared in the New Yorker a few years ago as “The Chapter: A History”), I’ve started investigating this question. We all have an intuition about chapters—how long they should be, their temporal scope, what they generally contain. Most of us, if given a paragraph chosen at random from a novel, could probably tell whether it began a chapter, ended a chapter, or fell somewhere in between. Yet could we say why? Could we explain our intuition to a computer? Sure, if we read a line like “and they rode off into the setting sun” we might guess that it belongs to the end of a chapter. But is the presence of a setting sun a distinguishing criterion for the end of a chapter? Do chapters usually represent a single day in narrative time? I decided to compute the linguistic fingerprint of the chapter, to get closer to understanding what it is.

First, I gathered as many novels as I could. Corpus-DB, the textual

corpus database I’ve been developing, makes it easy to get large

numbers of plain text files that match certain categories. At the moment

it contains all 50,000 or so texts from Project Gutenberg, and metadata

about these books gathered from Wikipedia and other sources. Using this

database, I was easily able to assemble corpora of several thousand

chaptered novels. I then broke these novels into chapters using two

methods. The first, using my tool chapterize, reads

the plain text files of the novels, looks for markers like “Chapter I”

using regular expressions, and divides the novels accordingly. The

second leverages hidden metadata in Project Gutenberg HTML files. If you

take a

peek at the source code of a Project Gutenberg HTML file, you’ll see

named anchors that look like <a name"c2" id=“c2”>=. These IDs

correspond to the chapter numbers—in this case, Chapter 2. By counting

the number of words of text that occur between these markers, we can

measure the chapter lengths of thousands of novels at a time. And by

extracting the text that begins and ends these chapters, we can find

language patterns that define a chapter’s boundaries. Here are some

trends I found.

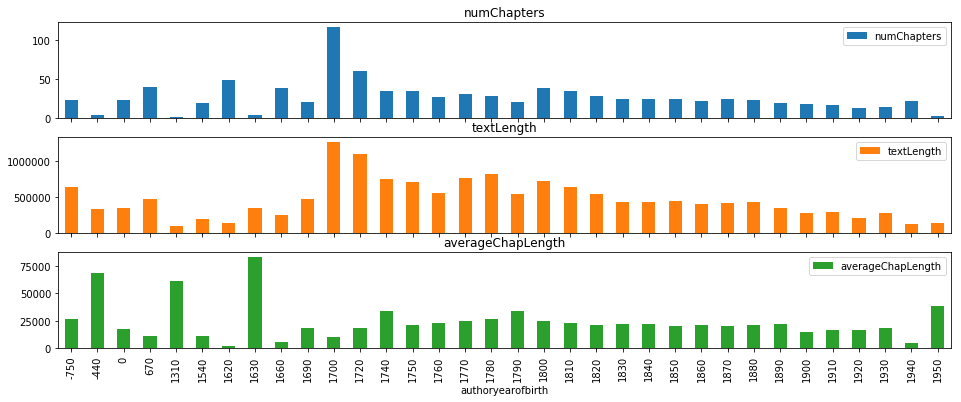

Chapter Statistics

Figure 1 shows the average number of chapters, the average text length, and the average chapter length for prose fiction works written by authors who were born in the decades shown. There is an amazing range of dates here, indicating the presence of some decidedly non-novelistic classical literature. (Project Gutenberg doesn’t maintain metadata about its texts’ original publication dates, but they do have author birth/death years, strangely, so I’m forced to use those as a proxy. This is a problem I’m trying to correct with Corpus-DB, but my solution isn’t quite ready yet.) This seems to show that by around the 19th Century, chapters are about the same length. They get a little shorter around the 20th Century, and are extreme and erratic before 1700, but I attribute this to the relative paucity of early (pre-1700) and late (post-1920) texts in the corpus, owing to factors like textual availability, canonicity, and copyright restrictions. It appears that novels have been getting shorter, however, and so there are also fewer chapters.

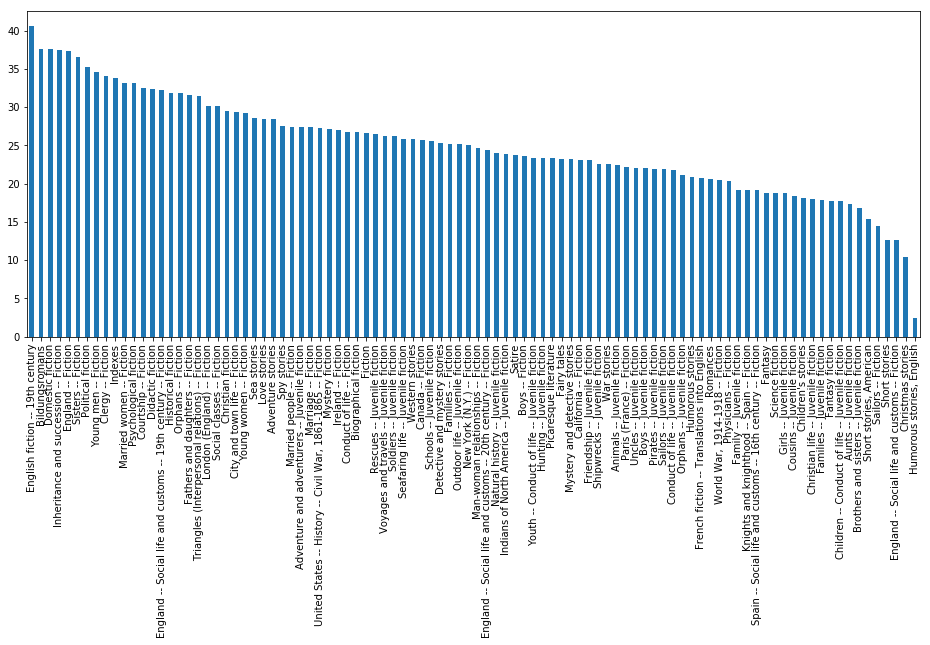

Figure 2 shows the average number of chapters per novel, sorted by the novel’s Library of Congress subject headings. Subjects with the most number of chapters are on the left, and subjects with the least are on the right. There are a few things of note here:

- The subject with the highest average is 19th Century English fiction, followed by Bildungsromans. Are Bildungsromans so long and chapter-filled because they have to represent the life of a person, rather than just one or two episodes in that person’s life?

- “Young men – fiction” is ranked slightly higher than “young women – fiction.”

- Civil war novels are ranked higher here than WWI novels. Is this a function of era (20th vs. 19th C), geography, or the nature of the wars themselves?

Of course, there are many more things that can be said about this chart. Please feel free to chime in, in the comments below!

Language Patterns of the Chapter

For the next experiment, I extracted the first paragraphs of each chapter from a few thousand novels, as well as middle paragraphs and final paragraphs. From there, I calculated TF-IDF scores for each word. TF-IDF just represents word frequencies, adjusted for the frequencies of those words in the corpus. In this case, it represents term distinctiveness to a paragraph group: how frequently a term occurs in first paragraph of a chapter, for instance, compared with how frequently it occurs in other paragraph categories. Here are the words distinctive of the first paragraphs of chapters:

morning, early, breakfast, afternoon, summer, autumn, winter, sunday, weather, october, arrival, june, september, saturday, awoke, situated, november, july, season, december

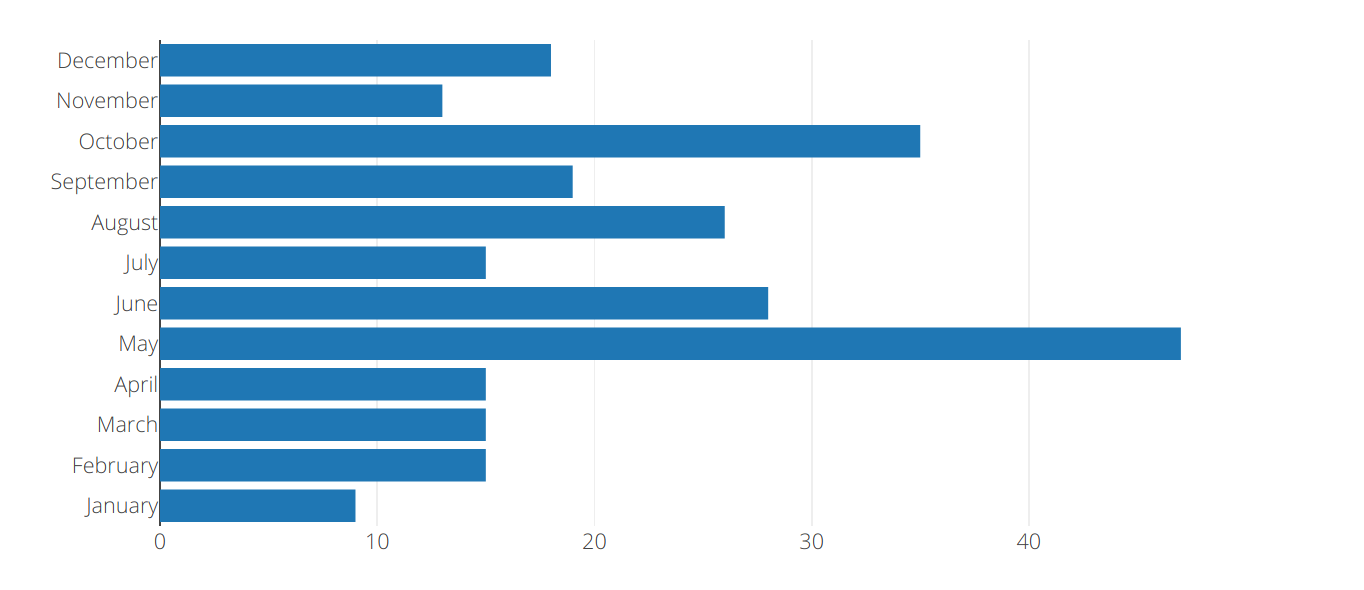

It seems that the first paragraphs of chapters set the scene: the season, the month, and the time of day (usually the morning). Just for fun, I computed the relative mentions of certain months from this small sample, and found that my intuition was correct: spring is over-represented in the beginnings of chapters, and winter is under-represented, with May as the most mentioned month, and January the least, as shown in Figure 3.

Here are the words distinctive of middle paragraphs:

replied, isn, ve, retorted, aren, hasn, mustn, shouldn, dey, inquired, doesn, haven, ye, wid, fer, wi, em, yer, protested, nothin

Some of these irregularities are attributable to the tokenizer, which is breaking up contractions in the wrong places, but others are dialect words. This seems to show that dialect—funny-spelled words—is not something that usually starts or ends a chapter. In Dickens, for instance, dialect is usually heard from characters intended to provide some kind of comic relief. These comic characters rarely have a narratorial role, it seems, and rarely bookend chapters.

Finally, here are the words distinctive of last paragraphs:

pg, kissed, farewell, bye, muttered, parted, disappeared, sank, page, asleep, strode, chapter, kiss, withdrew, homeward, sobbing, thanked, wept, murmured, prayed

There is a remarkably sad tone here in “sobbing,” “wept,” and “prayed.” Lots of goodbyes are happening here, as well. “Pg” and “page,” seem to be OCR artifacts, but is “chapter” a computing error, or the narrative voice, signaling the end of the chapter?

What do you think defines a chapter? Let me know in the comments.

Code

The code used to generate all this is in my GitHub repo called chapter-experiments.