Posted 2017-06-07

The house had a name and a history; the old gentleman taking his tea would have been delighted to tell you these things: how it had been built under Edward the Sixth, had offered a night’s hospitality to the great Elizabeth (whose august person had extended itself upon a huge, magnificent and terribly angular bed which still formed the principal honour of the sleeping apartments), had been a good deal bruised and defaced in Cromwell’s wars, and then, under the Restoration, repaired and much enlarged; and how, finally, after having been remodelled and disfigured in the eighteenth century, it had passed into the careful keeping of a shrewd American banker, who had bought it originally because (owing to circumstances too complicated to set forth) it was offered at a great bargain: bought it with much grumbling at its ugliness, its antiquity, its incommodity, and who now, at the end of twenty years, had become conscious of a real aesthetic passion for it, so that he knew all its points and would tell you just where to stand to see them in combination and just the hour when the shadows of its various protuberances—which fell so softly upon the warm, weary brickwork—were of the right measure. (James 2003, 60)

This single sentence is the longest of Henry James’s novels. Like the house it describes, it is copious, labyrinthine: an architectural wonder. At first glance, it is ugly, cumbersome, and even confusing, but upon rereading, one finds a “real aesthetic passion” for it and its “various protuberances.” The sentence begins by traversing several centuries in a just a few words, continues by covering a twenty-year personal history, and finishes with a cadenza that elongates time just enough to enable us to savor the certain slant of light illuminating the dear old house. James’s style, alive and beating in this sentence, has been the central subject of several complete volumes and countless articles. His sentences, in particular, have been much discussed. Their compounded clauses, digressions, and qualifications allow for temporal compressions and expansions. Their balance—or imbalance—is what has made them the subject of so much critical controversy. This study presents new methods for quantifying these properties of James’s sentences, methods which might also help to illustrate their appeal.

Dependency parsing is a method of computational linguistics and natural language processing that algorithmically infers syntactic dependencies between words in a sentence. Adjectives that describe a noun, for instance, are graphed as the noun’s dependents. Grammatical subjects and objects, similarly, are dependents of the main verb of a sentence. Subordinate clauses are dependents on the main verb, as well, and have their clausal subjects and objects as their own dependents. This study uses SpaCy, a new library for natural language processing written in the Cython programming language, and one of the fastest and most accurate available dependency parsers, to parse James’s sentences (Honnibal, Johnson, and others 2015). This study also uses a Python module I wrote called Sent2Tree, which parses SpaCy’s dependency graphs into standard tree structures, mathematical objects that can then be manipulated using tools like the ETE3 Toolkit, a library originally created for manipulation of phylogenetic trees (Huerta-Cepas, Serra, and Bork 2016). These tools, as we will discover, will allow us to understand the Jamesian sentence in new ways.

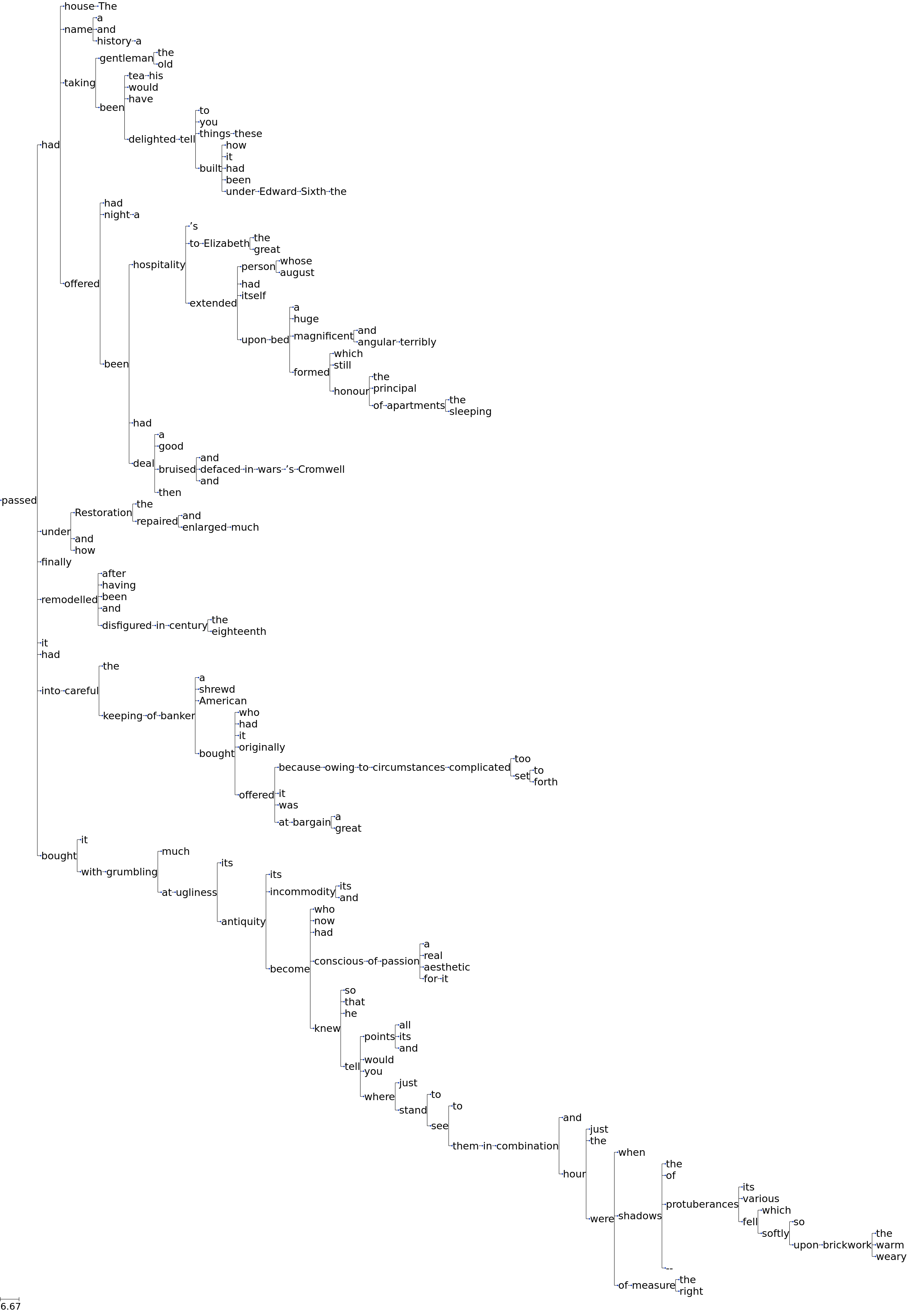

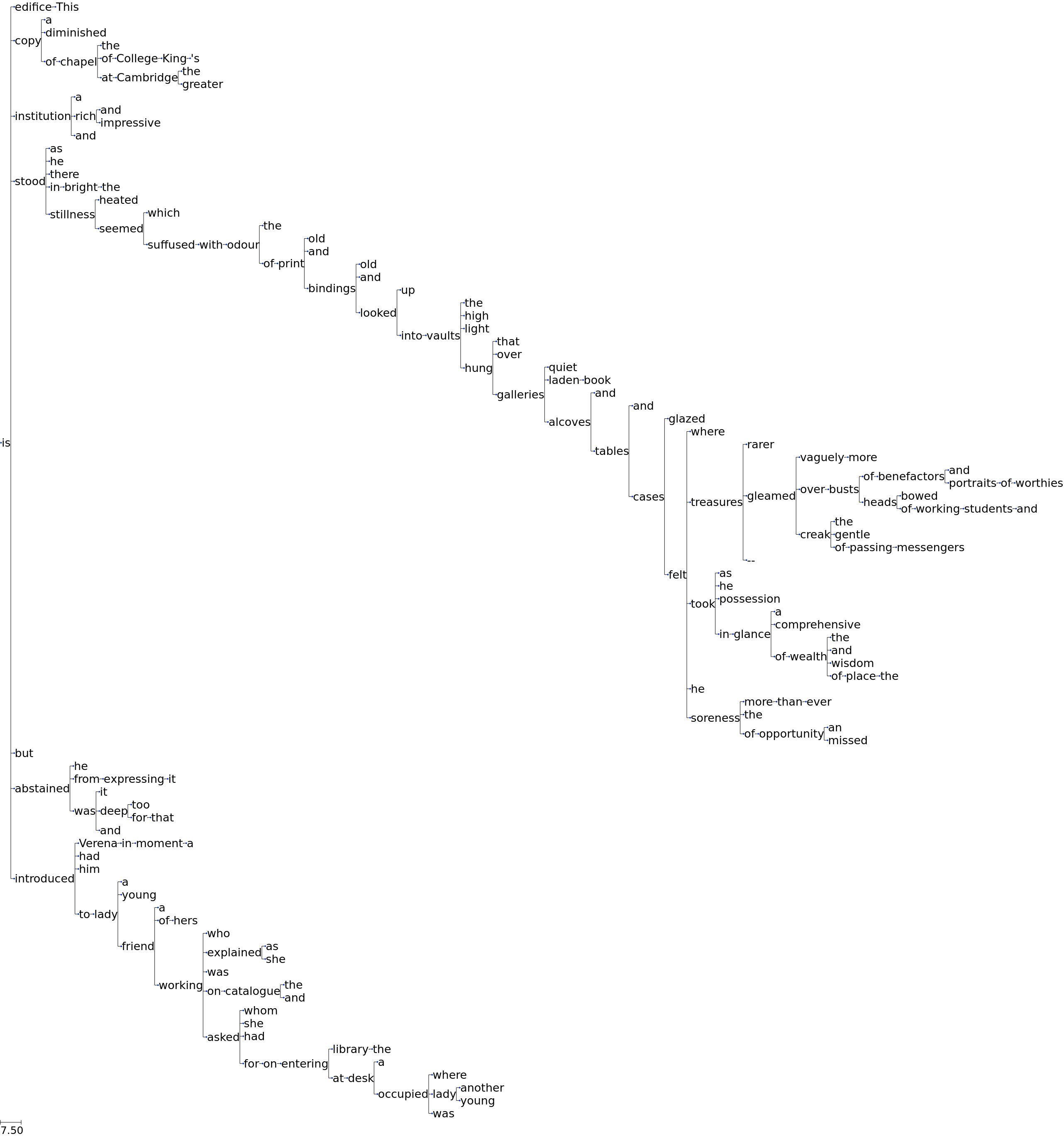

Figure 1 shows a visualization of a sentence tree created from parsing James’s longest sentence above with SpaCy and Sent2Tree. The SpaCy parser has inferred that “passed” is the fulcral verb in the sentence, a central verb, in a literal, if not figurative sense. The parser correctly identifies most of the clausal structures: the interlude about Edward the Sixth is identified as its own branch, and so are those about Elizabeth and Cromwell. The house’s Restoration and eighteenth-century histories are also their own branches, but top-level instead of dependent on “had.” The early history of the “American banker,” not yet revealed to be Mr. Touchett, is on a further branch, and his present history, with its digression into the house’s details and shadows, is the final branch. This segmentation might not be perfectly intuitive—an intuitive division might split the independent clauses on either side of the semicolon—but it nonetheless reveals many of the movements of the sentence: the periods of its histories, and the digression into more lingering, aesthetic language that constitutes the sentence’s finale. This figure captures both the relative balance of the sentence—its tidy list-like history—as well as its ultimate imbalance—its descent into the realm of the slow, minute, and sensory world of shadows and warm bricks.

Sentences in James’s Novels

While the sentence above is James’s longest sentence, and therefore exceptional, it is not anomalous. Sentences of similar complexity appear throughout James’s career, and not only in the later novels, when he is most known for this style. To test exactly where his longer sentences appear, I manually assembled a corpus of twenty novels: all of his novels except for The Other House and the posthumously published A Sense of the Past, both difficult to obtain in electronic form. I assembled the text mostly from editions found at Project Gutenberg and file:henryjames.co.uk, and they represent a mix of American and British editions. The length, in word counts, of each sentence I then quantified, and aggregated into a histogram of ten equal-sized groups.

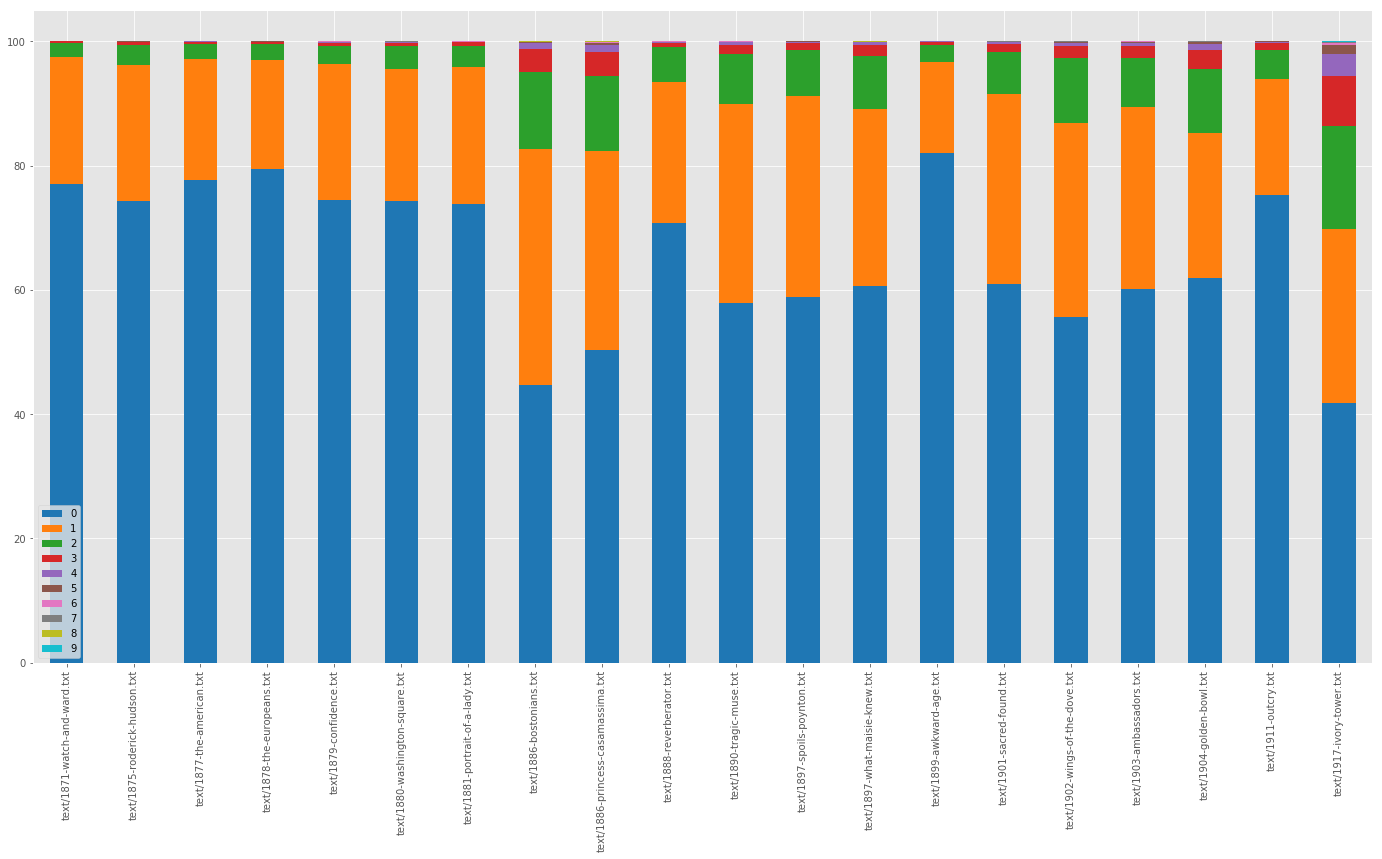

These groupings, plotted chronologically according to novel, are shown in Figure 2. Bars with an index of zero represent the shortest decile of sentences in that novel, and bars with an index of nine represent the longest decile. Broadly speaking, the strongest trend is the one that divides the so-called Jamesian early style from the late, which here seems to happen during the five-year gap in James’s novel publication streak between 1881 and 1886, during which he travels extensively to America and continental Europe (Haralson and Johnson 2009, 8–9). Whether his travels, his wife Alice’s cancer diagnosis, or other personal factors are responsible for this is beyond the scope of this study, but the fact remains that James’s style after 1886, at least expressed in sentence length, seems to have changed. The only exception is The Awkward Age, which might be explained by noting its highly dramatic structure (James later adapted it into a play), and thus its high incidence of dialogue.

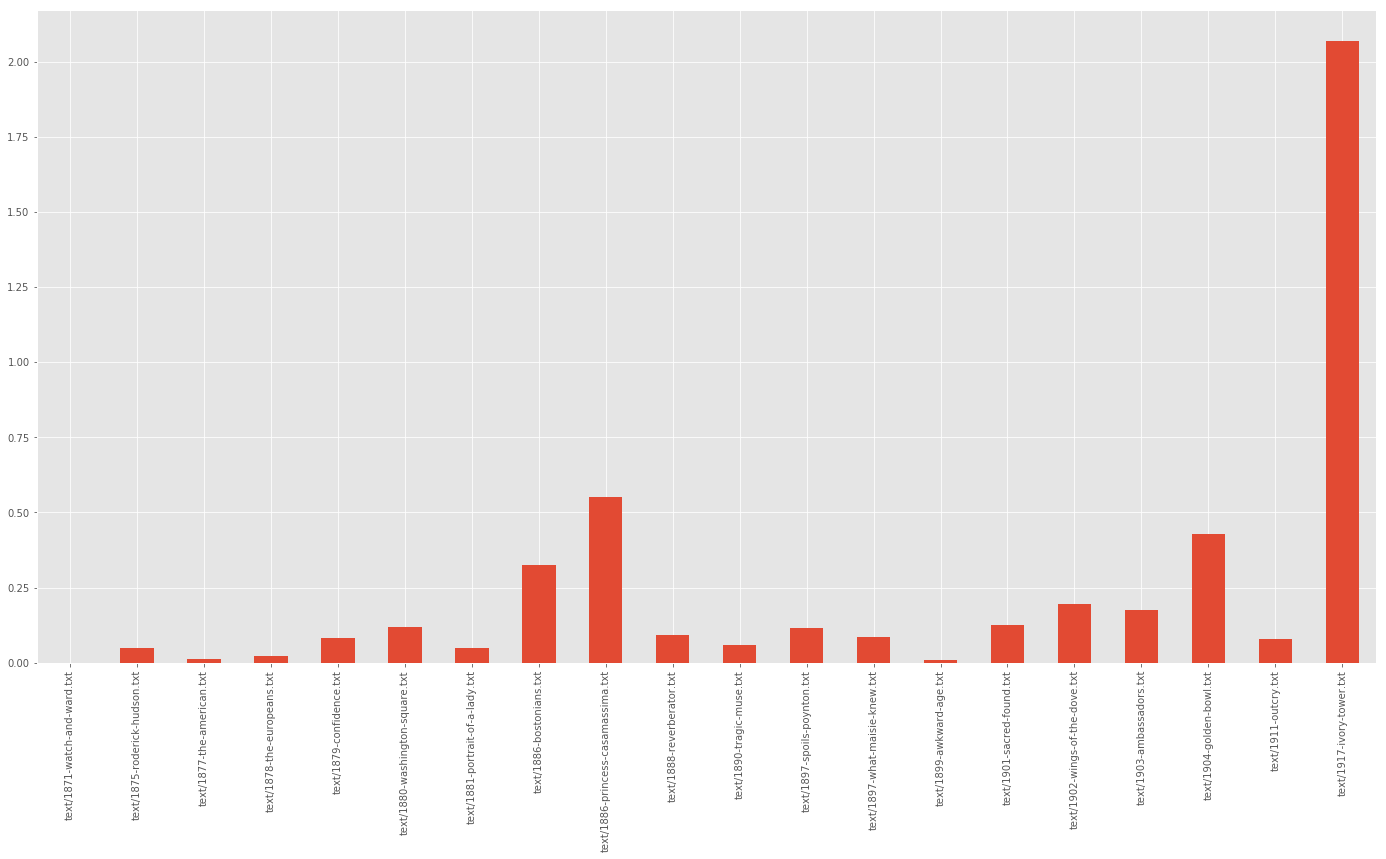

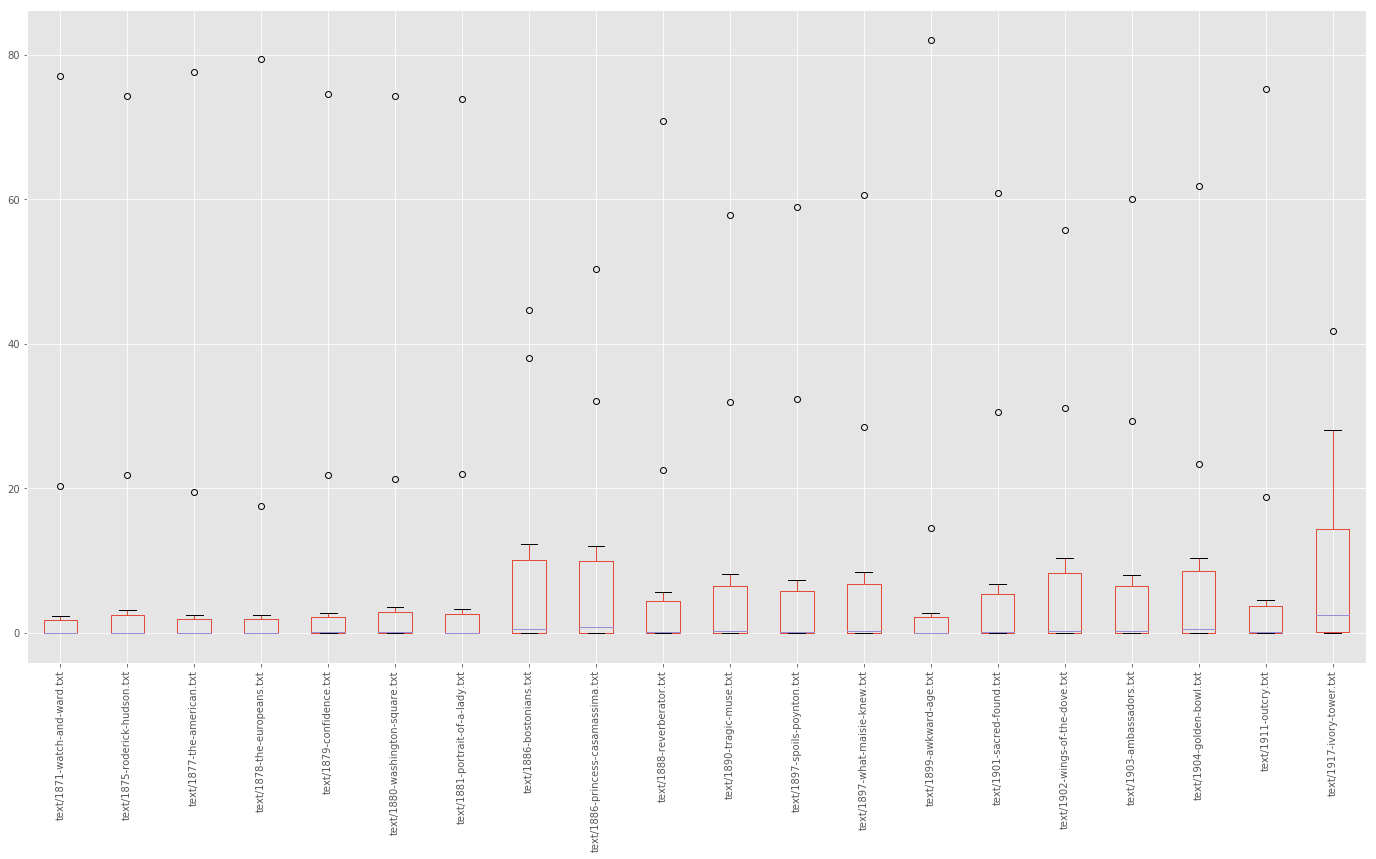

Figure 3 shows the same series, but only the sums of deciles 5-9, corresponding roughly to very long sentences. In this view, which as the scale shows, only represents two percent of the whole, very long sentences like the one quoted above seem most likely to appear in the poshumously published The Ivory Tower, followed by Princess Casamassima, The Golden Bowl, and The Bostonians. Finally, Figure 4 shows a box plot of the same series, more clearly showing the properties of each distribution of sentence lengths. Here, the early/late style divide is most apparent in the division between the box sizes, representing the interquartile ranges of each distribution. Again, apart from the posthumous novel, the most notable outliers are the 1886 pair of Princess Casamassima and The Bostonians. The sentence below is from The Bostonians:

This edifice, a diminished copy of the chapel of King’s College, at the greater Cambridge, is a rich and impressive institution; and as he stood there, in the bright, heated stillness, which seemed suffused with the odour of old print and old bindings, and looked up into the high, light vaults that hung over quiet book-laden galleries, alcoves and tables, and glazed cases where rarer treasures gleamed more vaguely, over busts of benefactors and portraits of worthies, bowed heads of working students and the gentle creak of passing messengers–as he took possession, in a comprehensive glance, of the wealth and wisdom of the place, he felt more than ever the soreness of an opportunity missed; but he abstained from expressing it (it was too deep for that), and in a moment Verena had introduced him to a young lady, a friend of hers, who, as she explained, was working on the catalogue, and whom she had asked for on entering the library, at a desk where another young lady was occupied. (James 2006a)

This 217 word sentence, James’s second longest, shares much with the longest sentence. Like the longest, its principal subject is a building. Like many of James’s characters, and indeed James himself, the building is somehow both American and European: the Harvard library, but also a Cambridge chapel. Furthermore, like the previously quoted sentence, it is a topography of a daydream. Though not a journey through time, it is a journey through space, an admiring pan through the library that nonetheless causes him deep “soreness.” This sentence does more than merely describe the library, however, for it moves straight in to the next action: “in a moment Verena had introduced him to a young lady.” The fluidity of this transition is underlined by the immediacy signaled by “in a moment,” which indicates that a sharp temporal shift has taken place. Time, that had been allowed to flow aimlessly and viscously across the objects of the library, now, “in a moment,” snaps back into place, and we again reach the staccato rhythm of action: “a friend of hers / who / as she explained.”

Figure 5 shows a visualization of the parsed sentence quoted above. The parser divides the sentence into seven branches. The first is the subject of the sentence; the second, a comparison with the Cambridge capel; the third is the reverie that takes Basil along the objects in the library. The first length of this branch shows the chain-like anaphoric structure in the string of objects connected with “and” and qualified with “that.” This shoot then blossoms into a new structure on the verb “felt,” which introduces Basil’s subjectivity. The branches below parenthetically qualify that subjectivity (it was too deep for expression), and bring the reverie to a close with the introduction of the young librarian. Overall, this structure is one of a digression: a movement into the sensory world of the aesthetic, followed by a movement back into the world of people and action.

Characteristics of the Long Jamesian Sentence

The two sentences we have seen so far, from different novels, exhibit many of the same characteristics. They both expand and contract the reader’s experience of time over the course of the sentence. Their syntactic structures have young, thin shoots, as well as broad, leafy, tree-like formations. But are these sentences characteristic of James’s long sentences more generally? To test this, I first divided all of the sentences from this corpus of James novels into two groups: those with fewer than thirty-four words, and those with thirty-four or more words. This number was calculated to produce a relatively balanced corpus containing roughly 1.6 million words from both categories. I then removed punctuation from the corpus and lemmatized the words, transforming plurals to singulars, and conjugated verb forms to their bare infinitives. These wordlists I then adjusted for the frequency in their categories, and compared with one another, to produce lists of words that are distinctive of each. I repeated this process, using groups of sentences with and more than 100 words, to generate lists of very long sentences, as well. To ensure comparisons of equal word counts, I randomly sampled from the list of shorter words until reaching the word count of the larger, repeating the process three times, and taking the mean of the results.

The most distinctive lemmas of James’s long sentences include many that seem appropriate to aestheically sensible, objective descriptions. There are architectural words, such as place and room; the lemmas distinctive of very long sentences add window and light. These lists are full of adjectives describing size or magnitude: great, small, high, low, and little. Markers of time like hour, second, evening, and occasion are also here. The sensory words sense and feel appear in these lists, alongside the more legal lemmas particular, effect, and fact. There are also indicators of a curious, interrogative mood in question and interest.

In contrast, the lemmas distinctive of short sentences seem appropriate to action: say, speak, tell, ask, look, and come. There are also the cognitive states of think and know, the anticipatory want and shall, and finally the almighty verb be. While the lemma Miss is distinctive of long sentences, the titles Mr, Mrs and Madame all appear in the list of words distinctive of short sentences. This suggests that James pays more lingering, wandering attention to his unmarried female characters, while his married female characters are more pragmatic, and prone to action. Similarly, the character names Horton and Hyacinth, from The Ivory Tower and Princess Casamassima, respectively, appear characteristic of long sentences, while Rowland, Nick, and Isabel of Roderick Hudson, The Tragic Muse, and The Portrait of a Lady are distinctive of short. This suggests that James allows characters like Hyacinth more meandering narrativistic interiority than characters like Isabel.

I conducted a few more experiments to determine the properties of James’s long sentences. The first dealt with the position of long sentences within their novels. My hypothesis was that long sentences seem likelier to to appear earlier than short sentences. This is only weakly true. The mean start location for a long sentence is at 51% of the narrative time of the novel, while the mean location for a short sentence is at 49%. This trend is somewhat magnified using very long sentences: they appear at 45%.

The second experiment concerned the logarithmic probabilities of the words in each category. This measurement, a built-in feature of the SpaCy library, calculates the probability, in log scale, of words occurring in a three billion-word corpus of modern English. If the probability is low, then the sentences contain improbable words, such as “incommodity” of this paper’s epigraph. My hypothesis was that longer sentences would contain more improbable words. This also proves to be true. The mean log probability of long sentences are about .16 lower than that of short sentences, and this difference is about .3 for very long sentences, about 30% of an order of magnitude.

Sentence Balance

To speak of a sentence’s “balance,” in terms of these tree structures, is to speak of a parsed sentence like a mobile, something that might hang over a baby’s crib, or be found in a Joan Miró painting. If Figure 1 were made of wire and equal weights, and if one were to pull it up by the verb “passed,” how would it hang? To measure this, I began by quantifying the total number of descendants of each first-level branch of the tree. In Figure 1, these branches are had, under, finally, remodelled, and so on. Then I took the standard deviation of all the elements in the resulting vector. This gives a measure of the sentence’s balance or imbalance: the relative differences between the total sizes of all of the sentence’s branches, nicknamed the “digression index.” The highest digression index (branch depth standard deviation) is 98, and it belongs to this sentence from The Tragic Muse:

The enemy was no particular person and no particular body of persons: not his mother; not Mr. Carteret, who, as he heard from the doctor at Beauclere, lingered on, sinking and sinking till his vitality appeared to have the vertical depth of a gold-mine; not his pacified constituents, who had found a healthy diversion in returning another Liberal wholly without Mrs. Dallow’s aid (she had not participated even to the extent of a responsive telegram in the election); not his late colleagues in the House, nor the biting satirists of the newspapers, nor the brilliant women he took down at dinner-parties–there was only one sense in which he ever took them down; not in short his friends, his foes, his private thoughts, the periodical phantom of his shocked father: the enemy was simply the general awkwardness of his situation. (James 2006b)

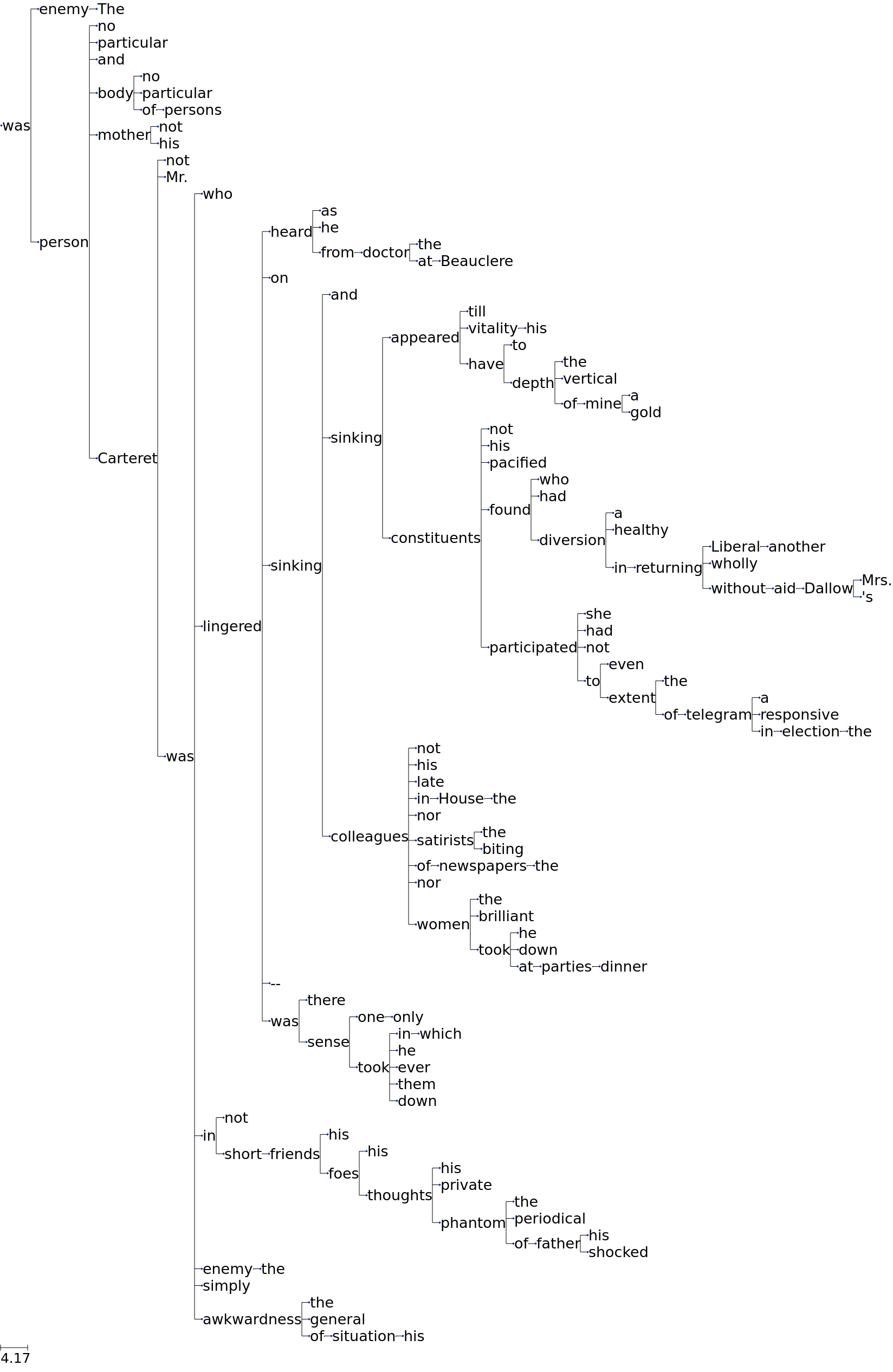

As shown in Figure 6, the syntactic structure of this sentence is extremely unbalanced, at least according to the SpaCy parser. It balances the subject “the enemy,” along the fulcrum “was” with a 139-word object. SpaCy parses some of these dependencies incorrectly, of course: “constituents” is dependent of “sinking” here, which is actually a wholly separate clause. Nonetheless, SpaCy captures the spirit of this sentence, which is a via negativa seeking to explain the nature of Nick’s abstract “enemy” in terms of what it is not.

At each of these negative comparisons, James lingers, exploring each to the fullest, seemingly without regard for the root intention of the sentence. At each, the reader is left wondering whether any one of these potential enemies might be a legitimate threat, after all. As in the sentence from The Bostonians, this is a list of what might have or what could have been. Just as Basil looks at the objects in the library with the “soreness” of “an opportunity missed,” Nick’s would-be enemies are aggregated here as ghostly threats: not true enemies, we are explictly told, but anxieties nonetheless. As with both of the previously examined sentences, there is also a time compression that happens at the end of this reverie, ushering us quickly back into the rapid pace of action: the indulgent digressions on Mr. Carteret quickly give way to a list of short expressions, signaled by the rhetorical “in short”: “his friends / his foes / his private thoughts.” The anaphoric repetition of “his” intensifies the rhythm of the sentence, and gives it an almost poetic meter. All of this functions as a crescendo which serves to contrast with, and highlight, the short, punchy clause that follows: “the enemy was simply:”—we pause on the colon, awaiting the definition—“the general awkwardness of his situation.”

Breadth-First Quantifications of Sentence Trees

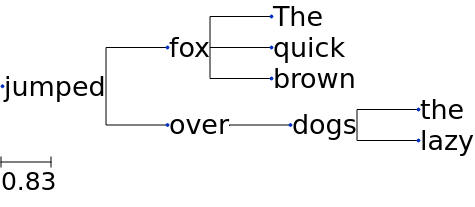

In addition to sentence balance, which measures the depth of each first-level branch by counting their total descendants, we might also employ a breadth-first approach to the numerical representation of sentence trees, one that quantifies the number of branches at each level of depth. Figure 7 shows an example sentence, “the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dogs,” parsed with SpaCy. A breadth-first quantification of this sentence would return the vector [1, 2, 4, 2], since there is one word at the root (“jumped”), two at the first level (“fox” and “over”), four at the second, and two at the last. When we average these vectors for every sentence in a novel, we can represent the average sentence structure of a novel.

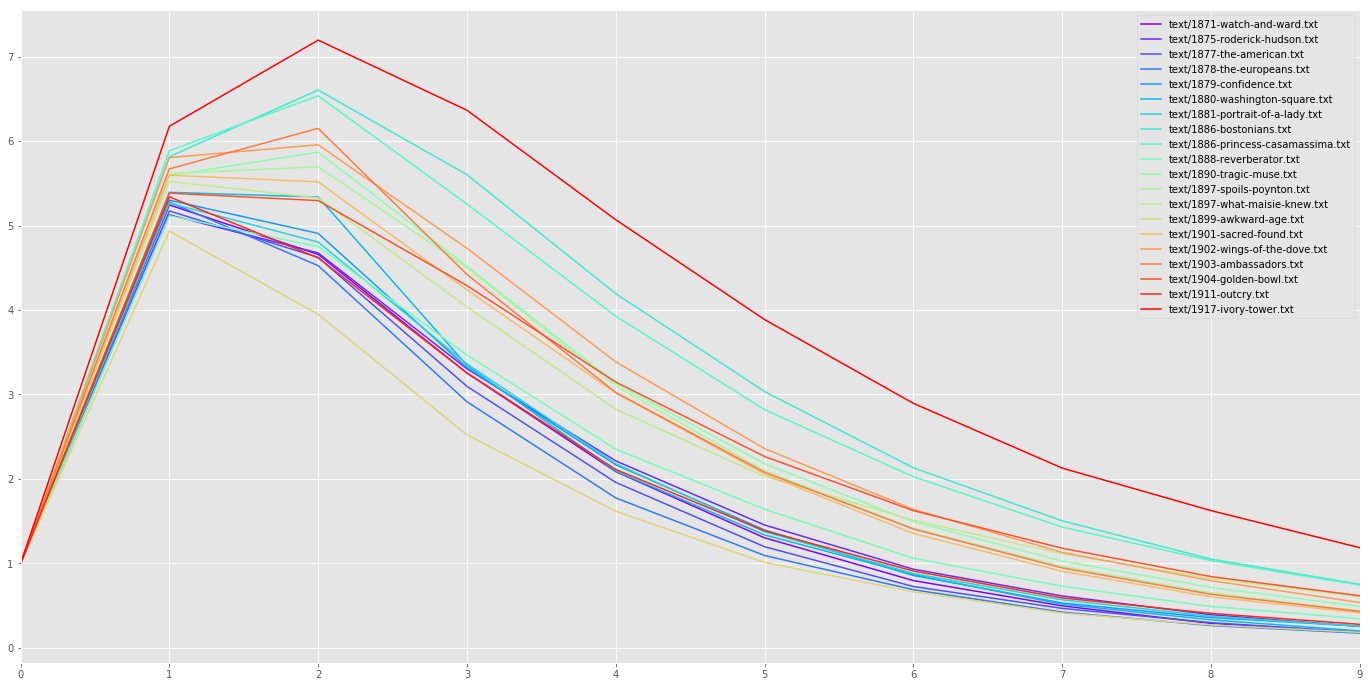

Figure 8 shows these average vectors for the corpus of James novels. The X axis represents the level of the sentence tree, and the Y axis represents the number of nodes at that level. It appears that the sentence structures in James cluster chronologically. Overall, the general chronological trend is one that tends toward greater syntactic complexity. The most cohesive group is the purple and dark blue cluster of lines that represent James’s early work, 1871-1881. Next, there is a much wider band (suggesting greater variety in sentence structure) in orange and green that corresponds to James’s middle and late years. Next, there is the pair The Bostonians and Princess Casamassima, both written in 1886, that stand on their own in light blue. Finally, the unfinished novel The Ivory Tower is in its own category altogether.

Conclusions

James’s long sentences, the artistic merit of which have been hotly debated among critics, are masterful monsters. Their structures allow for wandering reveries and digressions to be set free and then reigned in; their energies are unbridled yet ultimately, neatly framed. Their greatly varying rhythms take us effortlessly from the lingering eye of an artist, to the voice of a pragmatic narrator, while simultaneously expanding and contracting the readerly experience of time. By dependency parsing these sentences, converting these objects into tree-structures, and quantifying their mathematical properties, we achieve a more accurate numerical representation of James’s style than has be previously been possible. These techniques—measures of sentence balance or digression, and breadth-first quantifications—might be added to the suite of tools that comprise authorship detection, or forensic text analysis more broadly, since authorial style, at least as evidenced in James’s bibliography, seems here to shine through.

Works Cited

Haralson, Eric L., and Kendall Johnson. 2009. Critical Companion to Henry James: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing.

Honnibal, Matthew, Mark Johnson, and others. 2015. “An Improved Non-Monotonic Transition System for Dependency Parsing.” In EMNLP, 1373–8. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/D/D15/D15-1162.pdf.

Huerta-Cepas, Jaime, François Serra, and Peer Bork. 2016. “ETE 3: Reconstruction, Analysis, and Visualization of Phylogenomic Data.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (6): 1635–8. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw046.

James, Henry. 2003. The Portrait of a Lady. New York: Penguin.

———. 2006a. The Bostonians, Vol. II (of II). http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/19718.

———. 2006b. The Tragic Muse. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20085.