Posted 2016-01-25

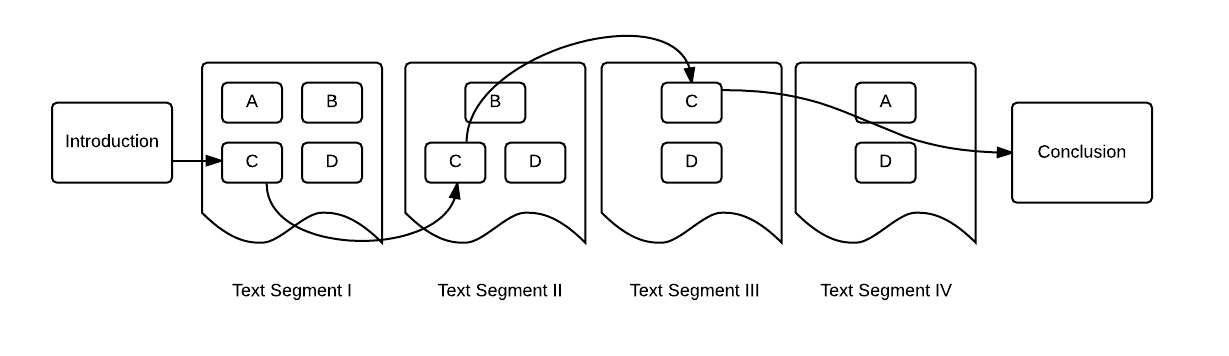

Works of literary criticism are typically built around their central arguments. The argument is often an opinion about a theme, function, or other textual attribute, and it is presented along with textual evidence that supports it. This usually means that a critical work closely examines textual details that are relevant to its thesis, while moving past or even ignoring less relevant details. Figure 1 shows a simplified illustration of this process. If each segment in the primary text contains details of types A, B, C, or D, a typical critical work will select one or more of these details for its analysis, while other details remain either less examined or fully unexamined.

There is nothing inherently problematic with this style of criticism—the thread that ties together these elements is that which makes the critical work enjoyable and easy to follow. This is also the structure that helps a critic to outline his or her contribution to the discussion: “Critic X discusses textual element A, and critic Y discusses textual element B, but they’re both ignoring the key to understanding the text, which is element C.” This can be a reasonably satisfying line of reasoning, but what if there were a more inclusive, less centralized way of talking about a text? Could we imagine a pluralist, iterative style of literary criticism? Would such a style be useful, or even desirable?

First, it is necessary to admit that this is not a new idea. What I will be calling “iterative criticism” here is present to some degree in any metaliterary work that gradationally catalogs, maps, or annotates a literary text. One such work is Don Gifford’s monumental Ulysses Annotated, a book of annotations for James Joyce’s Ulysses. Staggering in the breadth of its scope, it analyzes the novel on the level of the word and phrase, to such an extent that its own length exceeds that of its primary text. As a non-narrative work that refrains from privileging any particular reading of the text, it can be read non-linearly: a reader interested in, say, the third word of Chapter 3 can simply find the relevant annotation and start reading. This property is probably that which has led to its being given the enigmatic Library of Congress subject heading “Joyce, James — Dictionaries,” rather than “Joyce, James — Criticism,” like most other Joycean critical works. But Gifford’s volume remains critical, despite the way works of annotation are often (quite literally, one might say) marginalized.

Another notable work of iterative criticism is Roland Barthes’s S/Z. Subtitled “an essay,” it is a book-length analysis of Honoré de Balzac’s short story “Sarrassine” with a nearly phrase-level focus. Barthes divides the story into 561 textual units he calls “lexias,” some of which contain a few sentences, and some which contain just a few words. Each of these lexias he discusses in detail, according to five “codes,” or groupings of annotations: hermeneutic, proairetic, semic, symbolic, and referential. A typical annotated lexia looks like this:

- Nobody knew what country the Lanty family came from, ★ A new enigma, thematized (the Lantys are a family), proposed (there is an enigma), and formulated (what is their origin?): these three morphemes are here combined in a single phrase (HER. Enigma 3: theme, proposal, and formulation).

Here, Barthes catalogs the emergence of “Enigma 3,” belonging to the hermeneutic code (“HER”). This enigma will make several more appearances in Barthes’s essay, the set of which forms a critical narrative in miniature. While S/Z is certainly meant to be read linearly, from beginning to end, these codes and enigmas form a network of non-linear subnarratives that provide alternate trajectories. In fact, one could almost call S/Z a proto-hypertext, in that its layering and self-referentiality provide a multiplicity of pathyways through the critical discourse. According to a 1994 definition by computer scientists Frank Halasz and Mayer Schwartz, hypertext provides “the ability to create, manipulate, and/or examine a network of information containing nodes interconnected by relational links” (30). This is precisely what S/Z accomplishes. One might even imagine that if Barthes had experience with a hypertext language like HTML, the codes and themes he cites might be linked together technologically as well as textually. That is one of the goals of the following experiment.

The Experiment

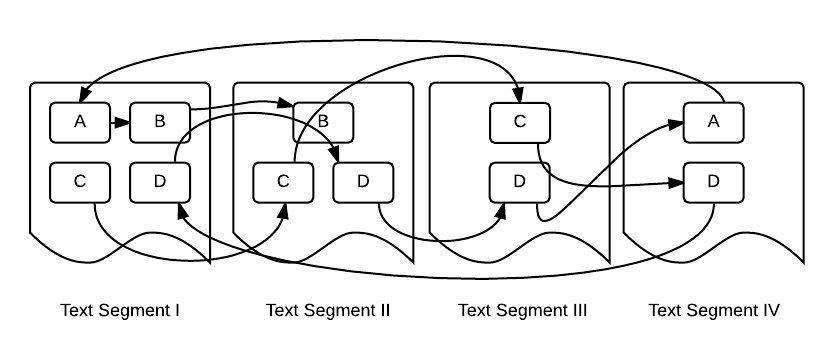

The following is an experiment in iterative literary criticism, where the text of Katherine Mansfield’s story “The Garden Party” is broken into 205 Barthesian lexias, annotated, and tagged. These tags are then linked to each other, forming miniature topic-based critical works. Clicking on a tag scrolls the page to the next annotation with that tag, and if there are no more, the page loops back to the first. A reader interested, in say, the semiotics of flowers in “The Garden Party” might read an annotation tagged “flora”, while a reader interested in gender dynamics might choose the tag “sexuality.” Since many lexia have more than one tag, the reader may switch between related tags once annotations with their first chosen tag have been exhausted. This effectively creates a non-linear critical work that more resembles a decision tree than a straight line. In this way, the reader effectively assembles his or her own critical narrative in the act of reading. A revised flowchart for this style of criticism might look something like Figure 2.

One of the advantages of this iterative style, compared with the narrative style, is that it opens the textual field to the greater possibility of surprises. New details emerge that might have otherwise been elided had the detail needed to fit into a prose paragraph, and the paragraph into an overarching argument. The two-column format used below privileges no particular reading, and as such, it allows for minority readings—critical theories that may not have enough textual evidence to be made into a standard-length journal article—to have equal status with majority readings.

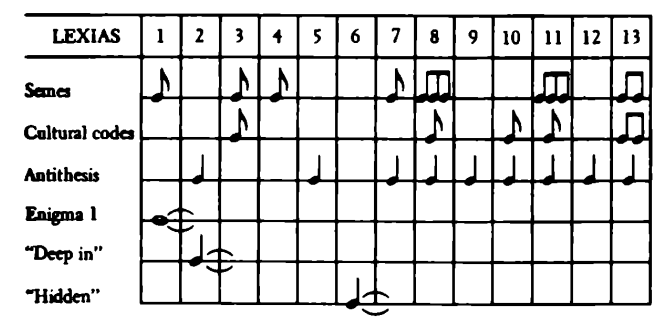

Another advantage of this style is that, by cataloging the appearance of textual themes, tensions, and images chronologically—that is, charting their occurrences according to where they happen in the story—we can derive a better picture of how those literary elements unfold, and where they disappear. To Barthes, this is the music of the text, which he charts literally in Figure 3.

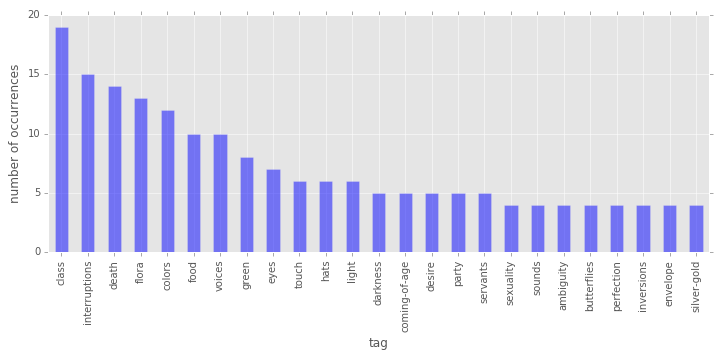

Rather than use semes and cultural codes, however, this edition of “The Garden Party” is tagged nonhierarchically, using roughly fifty tags. The types of these tags range everywhere from color images like “green” and “black” to the story’s treatment of social class, given by the tag “class.” Some significant objects, such as Laura’s hat are tagged, as well as the story’s envelope(s). A full list is given in the iPython notebook used to generate tag statistics. Figure 4 shows all tags with more than three occurrences, sorted according to how often they are used.

The tag that appears the most often is “class.” This is unsurprising, given the story’s overt treatment of social class. The second most frequent tag is “interruptions,” which charts both syntactic truncation (“isn’t life” of L204, for instance) and proairetic truncation, such as the interrupted breakfast of L7. Other notable tags include “flora,” used whenever literal flowers appear, or when floral metaphors are used, such as in L150. These tags can help to track trends, themes, and moods as they unfold in the chronology of the story.

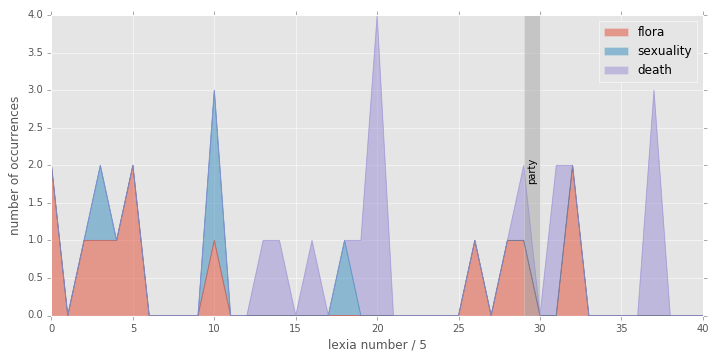

Figure 5 shows three of these tags: flora, sexuality, and death, plotted according to where they occur in the story. Flora and sexuality tend to collocate, as one might expect, and for the most part, references to flowers and references to death are fairly separate, with the exception of the group that occurs around the time of the party. (The X values in this chart correspond to the lexia numbers divided by 5, grouped here for smoothing.) Upon closer examination, it turns out that these are some interesting collocations of floral and morbid imagery. One is Laura’s hat, black as if in mourning but “trimmed with gold daisies”; another is the floral metaphor of the dying afternoon: “the perfect afternoon slowly ripened, slowly faded, slowly its petals closed” (L150).

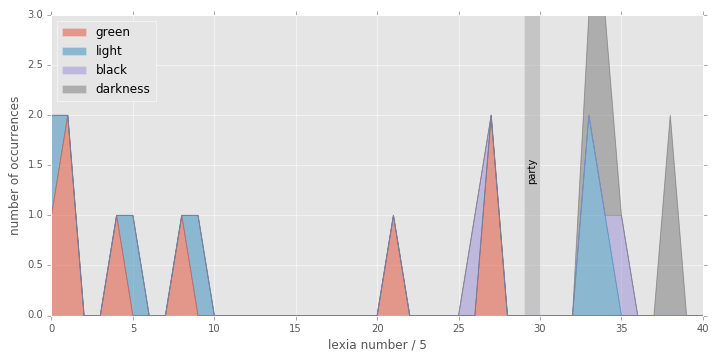

With colors, too, we find interesting collocations, as shown in Figure 6. On the whole, references to greenness or green things (the grass, bushes, and turban, for instance) collocate with the morning and with preparations for the garden party. References to light occur mostly in this portion of the story, too, and references to black and darkness mostly happen after nightfall. However, there are two notable surprises here: the collocation of green and black at 27, directly before the party, and the strange combination of light, black, and darkness around 33. The first corresponds to the black hat of L137 followed by the green band and green tennis court of L140. One might read the appearance of the black hat as a hint of the mourning scene to come, and the greenness of the garden party as the apex of the green imagery that has been building during the party’s preparations. The second unexpected collocation, that of light and darkness at 33 in this chart, is the chiaroscuro generated by the dusky slant of light that makes the road “gleam white” and throws a “deep shade” on the cottages (L171). Based on this chart alone, it might be able to guess the timeframe of the story (in classic modernist fashion, it takes place in a single day) as well as the time of sunset (around location 35 in the chart).

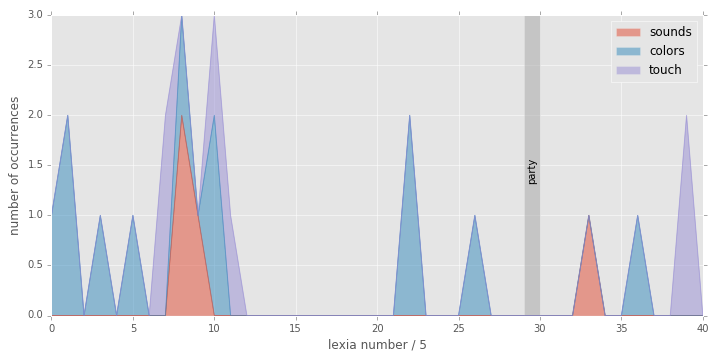

Sensory descriptions might also be useful to study quantitatively. Figure 7 shows tags of sounds, colors, and touch. A few examples of these are the “chuckling absurd” sound of the piano at L47, the repetition of “pink” in describing the lilies at L53, and Laura’s nibble of her mother’s ear at L58. Most of the sounds, colors, and touches occur in the first quarter of the story, highlighting the sensory richness of the morning preparations, which contrast greatly with the “dark,” “oily” imagery of the cottages. Notably, however, there are none of these impressions during the party itself, or immediately before or after. Only Laura’s memory remains, when she recalls “it seemed to her that kisses, voices, tinkling spoons, laughter, the smell of crushed grass were somehow inside her. She had no room for anything else. How strange!” (L172).

Many more quantitative literary analyses are made possible by this iterative approach. For a fuller list of tag comparison charts, and to run the Python 3 code against arbitrary collections of tags, see the iPython notebook used to generate these charts.

Iterative criticism is not meant to replace narrative criticism. Nor is it meant to represent the circumscribed totality of what can be said about a literary text. There are some birds-eye readings that simply do not fit into the sentence-level focus given here, and that is especially true of historical and biographical readings. But the insight gained from this inclusive, step-by-step technique might help us to discover things that the teleology of narrative criticism hides. It might help us to, in Barthes’s words, “remain attentive to the plural of a text” (11).

Textual Notes

The text of Katherine Mansfield’s story presented below is derived from the GITenberg edition of The Garden Party and Other Stories. The plain text was marked up using the Extensible Markup Language (XML) format of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI). This format, the standard markup language for archival literary projects, is a semantic markup language—unlike markup languages like HTML 4.0, which describe how a text should look, i.e. =<i>The Garden Party</i>=, TEI XML describes what the text is, i.e. =<title>The Garden Party</title>=. This allows text segments to be selected based on their literary, rather than textual attributes.

The

TEI text is transformed to HTML using xsltproc and an

XSL stylesheet, and combined with this introductory text, which is

transformed from markdown into HTML using pandoc. The files are combined using sed, and the compilation process automated using

a

makefile written for GNU make. A

short jQuery script handles the interactive tag behavior.

Since the text has been broken into segments, pilcrow marks (¶) have been used to denote the beginnings of paragraphs as they appeared in the original text.

This edition has been made using exclusively free and open-source software. This text and the source code for this project is released under the GNU Public License v3, the full text of which is available in the included license.

Click on the link below to start reading the edition: