Posted 2015-03-12

“in the imitation of these twain–who as Ulysses says, opinion crowns with an imperial voice–many are infect.” –Nestor, Troilus and Cressida, Act 1, Scene 3.

The following describes an experiment in digital literary analysis, wherein dialog from Shakespeare plays was extracted, categorized, and statistically analyzed using a variety of methods. Dialog from Shakespeare’s kings, for instance, such as that of Lear and Claudius, was statistically compared with dialog from a number of other groups, like Shakespeare’s queens, servants, and fools, in an effort to computationally identify characteristic trends in the language of each group. This investigation concludes that relationships between these groups may be divined through this analysis, even suggesting class hierarchies and gender relations, but that these results are tenuous at best, and more fine-tuned analysis is required.

Extraction

Extracting dialog from a plain-text document would be a labor-intensive manual task, but an electronic text marked up in TEI XML is designed for easy computational manipulation of its elements. Thanks to the markup efforts of organizations like the Wordhoard Shakespeare, the Monk Project, and the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Digital Texts project, many classic works have been transformed into this machine-readable form, including 42 of Shakespeare’s plays. Since the dialog of these plays is assigned metadata that attributes it to its speaker, it thus becomes possible to automate the extraction of dialog. Each spoken line is rendered in XML roughly like this:

<sp who="Hamlet">

<speaker>Hamlet</speaker>

<l xml:id="sha-ham301055" n="55">

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

</l>

</sp>

Each line is thus enclosed in <sp> tags, each with the who attribute assigned to unique, regularlized

XML IDs corresponding to each character in Shakespeare. Since Hamlet is

the only character named Hamlet in Shakespeare’s plays, his XML ID is

simply Hamlet, but other characters are

given unique IDs. Since there are multiple ghosts in Shakespeare’s

plays, for instance, the ghost of Hamlet’s father is given the XML ID

ham-ghost. in the Wordhoard TEI

rendition.

Dialog Extraction

The Folger Shakespeare Library TEI files are extremely meticulously edited, with emendations and textual differences marked up, as well as metadata about the characters, such as their sex. These would be ideal documents to work with, except that the depth of the markup makes them unwieldy in more than one respect. For instance, whereas the Wordhoard Shakespeare dialog, as illustrated above, is marked up on the level of the line, the Folger Shakespeare TEI marks up every word, space, and punctuation mark of the text:

<sp xml:id="sp-0006" who="#FRANCISCO-HAM">

<speaker xml:id="spk-0006">

<w xml:id="w0000570">FRANCISCO</w>

</speaker>

<ab xml:id="ab-0006">

<lb xml:id="lb-00051"/>

<join type="line" xml:id="ftln-0006"

n="1.1.6" ana="#verse" target="#w0000580

#c0000590 #w0000600 #c0000610 #w0000620

#c0000630 #w0000640 #c0000650 #w0000660

#c0000670 #w0000680 #c0000690 #w0000700

#p0000710"/>

<w xml:id="w0000580" n="1.1.6">You</w>

<c xml:id="c0000590" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000600" n="1.1.6">come</w>

<c xml:id="c0000610" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000620" n="1.1.6">most</w>

<c xml:id="c0000630" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000640" n="1.1.6">carefully</w>

<c xml:id="c0000650" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000660" n="1.1.6">upon</w>

<c xml:id="c0000670" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000680" n="1.1.6">your</w>

<c xml:id="c0000690" n="1.1.6"> </c>

<w xml:id="w0000700" n="1.1.6">hour</w>

<pc xml:id="p0000710" n="1.1.6">.</pc>

</ab>

</sp>

This level of detail allows for great precision in cases where, say, one would need to mark up textual difference on the level of a single character, but it makes these texts much more difficult to work with on the macro level, mostly owing to their size. At several megabytes each, searching them, displaying them, and transforming them in the browser takes a considerable amount of time. The XSL transformation that converts the XML into XHTML for display in the browser, for instance, takes a modern browser on fairly capable hardware around 1-2 minutes to display.

Instead of using the Folger Library TEI files, which required a considerable amount of XSL transformation, this approach used Wordhoard Shakespeare TEI “unadorned” files. Unlike the Folger files, these are not as heavily marked up, and so they are much easier to work with. Furthermore, there are 42 plays in the Wordhoard corpus, whereas there are fewer than half that number currently in the Folger corpus. Some useful metadata, such as the sex of the characters in the cast list, are missing from the Wordhoard files, but the usefulness of their brevity outweighs any inconvenience caused by that omission.

To parse the XML, a

python command-line program was written. The advantage of

command-line programs is that they are interoperable–the output of one

program can be easily channeled to the input of another by using the

| operator, for instance. Similarly, the

output of a program can be written to a file using >, or appended to a file using >>. This allows the user to write a single

command that would do the work of lots of pointing and clicking, and it

allows for the user to interface that command with any other existing

command-line program in the operating system. Perhaps the biggest

advantage of this approach is that most command-line shells, like BASH,

which ships as the standard terminal in most varieties of Linux and Mac

operating systems, is that it supports wildcard expansion–using *.xml in place of a filename tells the shell

that you want to run your command over all the files containing the

extension .xml, which is incredibly useful

for working with large numbers of files, such as 42 Shakespeare

plays.

This python script parses all the XML files it is given, and iterates

over them, looking for sp tags with who attributes that match those in characters.txt, or another user-specified file

containing a comma-separated list of characters’ XML IDs. To extract all

of Ophelia’s lines from Hamlet, for instance, the user first creates a

file named characters.txt and gives it the

content Ophelia:

echo "Ophelia" > characters.txtThen the user runs the python program on the ham.xml TEI file of Hamlet, to extract the

dialog and save it to a text file called ophelia-dialog.txt:

python parse.py ham.xml > ophelia-dialog.txtTo extract all of Falstaff’s dialog from all 42 of the Wordhoard

Shakespeare plays (which is easier than specifying the three in which he

appears), and save that dialog to a file called falstaff-dialog.txt, these commands can be run

from within a directory containing all of the XML files:

echo "Falstaff1" > characters.txt

python parse.py *.xml > falstaff-dialog.txtIf the program is given a characters.txt file (or another file which the

user specifies) containing a comma-separated list of characters, it

outputs the combined dialog of all of those characters. It was therefore

possible to extract dialog from large groups of characters in this

way.

Character Lists

To comparatively analyze the dialog of Shakespeare’s characters, it was first necessary to assign categories for these characters. This proved to be a difficult problem, since this categorization can be very subjective–who is considered a comic figure by one critic may well be considered tragic or tragicomic by another, and the categories of these characters may (and often do) shift throughout the course of a single play. The categories I chose were “kings,” “queens,” “servants,” “gentlemen,” “gentlewomen,” “officers,” and “fools.” Although categories, none of them are precisely “categorical,” which is to say, none of them are completely unified and unambiguous.

To choose these characters, the Shakespeare character search engine at the Electronic Literature Foundation was used, which accepts a search term and outputs a list of characters in whose role descriptions that term occurs. These data had to be trimmed somewhat, since the word “king” appears in the description “servant to the King,” and thus the results of a search for the word “King” did not always return a list of kings. The “kings” and “queens” categories were probably the clearest to delineate, since most of the characters in these categories carry the titles of “king” or “queen.” Even with those, however, there were plenty of problematic cases. Would Oberon, the king of the fairies from A Midsummer Night’s Dream be considered a king, for the purposes of this study? If this study aims to discover class-specific language in Shakespeare’s works, then it could be argued that supernatural kings don’t represent this class structure, but rather that of the supernatural world they inhabit. On the other hand, if one interprets the supernatural world of the fairies as a projection of the earthly world, with all its hierarchies intact, then it is entirely reasonable to include Oberon among the kings. A complete list of all the characters is available in Appendix I.

The next category, “servants,” was populated by searching the character descriptions for the term “serv,” which returned words such as “servant” and phrases such as “in the service of.” All characters named “Servant” were included, as well as any any characters described as “servant to” another character. All characters described as “in the service of,” however, were not included, since they were almost all described as “gentleman in the service of” or “gentlewoman in the service of”, and therefore placed in the respective categories of “gentleman” and “gentlewoman.” Those categories, “gentleman” and “gentlewoman” were populated by searching for those terms.

The “officers” category contains officers, soldiers, “gaolers,” a sheriff, and a sentinel. Although these are slightly different roles, they are treated here as a single group, since that is often the way they are treated in the cast of characters–in Antony and Cleopatra, the group is described as “Officers, Soldiers, Messengers, and other Attendants.” Messengers were not included in this category, however, and neither were “other attendants,” because the goal here was to aim for a group that will be relatively unified in tone, which is this case hopes to be paramilitary.

The category “fools” was the most problematic. There aren’t enough fools in Shakespeare to make for a category large enough for statistical analysis, and so I’ve included both fools and clowns here. Although he admits they are related categories, Stanley Wells asserts that “Modern criticism distinguishes between the naturally comic characters, or clowns, such as Lance, Bottom, Dogberry. etc., and the professional fools, or jesters, such as Touchstone, Feste, and Lear’s Fool” (“Clown”). Whereas this may be a crucial distinction for criticism, I have nonetheless grouped the two together for pragmatic reasons. A more nuanced study might separate the two, but this investigation is focused on macro-categories for the sake of efficiency. Toward this end, I’ve used the list of fools from Wikipedia’s page (“Shakespearean Fools,” somewhat spurious, in parts, though inclusive), and supplemented it where necessary with search results for “fool” and “clown” from ELF.

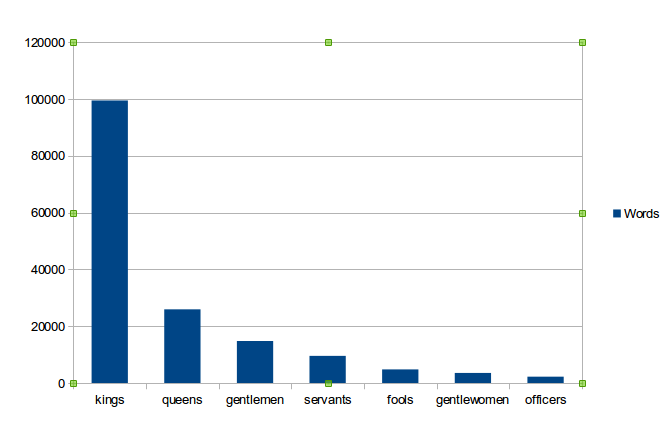

The biggest challenge with these categories is the variety of lengths among them. “Kings” was the largest category, containing 99,540 words, or over three Hamlets in length; “queens” is the second biggest, with 25,934 words; “gentlemen” is next, with 14,788; followed by “servants” at 9,554; “gentlewomen” at 3,530; and “officers” at 2,222.

That the smallest category contained only around two thousand words, and the largest contained almost 45 times that amount, meant that, for one, the probability of a given word appearing in the “kings” category did not depend solely on voice or stylistic concerns, but on the character’s opportunity to speak. We can say, (as I will soon, in fact, be saying) that certain words are characteristic of Shakespearean officers, and that there are certain words which they do not say, but much of this is dependent on the amount of text. Any judgement about the treatment of class or gender in Shakespeare, based on a computational analysis such as this, is in danger of conflating misrepresentation with underrepresentation. Servants may very well refer to their “master” and “mistress” frequently, but perhaps it is more that we rarely get a chance to hear them speak to the extent that we hear the kings and queens. Granted, a lot of this discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that so many of Shakespeare’s play are histories. One could hardly expect plays with titles like Henry VIII or Antony and Cleopatra to revolve around anyone but their titular roles.

With the

characters tabulated into categories, the tables were then exported

into CSV text files containing comma-separated lists of XML IDs. Here

is, for example, the contents of queens.csv:

Gertrude,Hippolyta,Titania,Cleopatra,CymbelineQ,

Elinor,Tamora,Hermione,Valoislsab,WoodvileEl,

MargaretQ,AragonCath,BoleynA,ElizabethBav

This list was then used to extract dialog from the plays by running the command:

python parse.py -c queens.csv *.xml > queens-dialog.txtCleaning Up the Texts

One of the features of this Python script is that it keeps the text encoded in unicode throughout. This means that any characters that do not appear in ASCII, like em-dashes or curly quotation marks, will not be mangled when they are extracted. Unfortunately, this also means that other tools, such as the University of Newcastle’s Intelligent Archive, will not be able to adequately interpret these unicode characters. When The Intelligent Archive encounters straight quotation marks, for instance, it dismisses them and does not consider them part of the word, but when it encounters curly quotation marks, it converts these into unusual characters like “œ” and leaves them attached to the word, thus generating wordlists containing corrupted words like “œthy.” To correct this, this command was run in the working directory:

for a in $(find . -name '-dialog.txt') ;

do iconv -f utf-8 -t ascii -c "$a" > "$a.ascii" ;

doneThis loop iterates over all the files ending in -dialog.txt (in this case, all the extracted

dialog), runs the Linux program iconv on

those files, and then writes them to new files, appending the .ascii extension. The -c flag tells iconv to throw out any characters that can’t be

converted into ASCII, which solves the issue with the Intelligent

Archive. Em-dashes and a lot of other punctuation are removed from the

texts during this process, but since punctuation isn’t an object of this

study, that doesn’t present a problem.

Statistical Analysis

Several varieties of computational statistical analysis were performed on the resulting texts. First, the texts were tokenized and split into segments using The Intelligent Archive. A few methods were used at this stage to lessen the impact of the word count discrepancy. In one set of tests, the texts were limited to the word count of smallest text, by setting the option “first X words of text.” The problem with this method, however, is that the first 2000 words from a king are likely to come from a single play. The analysis would then be comparing all the dialog of the servants and fools with, say, the character Henry VIII, instead of all the kings. This is a major problem, but also one that mostly affects the kings category. The smallest category isn’t affected by this at all. Another technique used to lessen this effect was to divide the text into 500 word blocks, and then choose a random set of four to eight blocks for analysis. Yet another technique was randomizing the lines in the texts themselves by filtering them through a command in BASH:

for a in $(find . -name '-dialog.txt') ;

do cat "$a" | sort -R > "$a.random" ;

doneThis loops over all the extracted dialog text files, writes their

contents to the standard output with cat,

sorts the lines by random (-R) criteria

with the sort command, and writes them to

new files.

All of these techniques are problematic in some way. If, say, the analysis shows that the word “and” is the most common word in the servants category, and that number is much lower or higher in another category, can we say with any certainty whether this phenomenon is an effect of style or voice? It seems equally as likely that, even despite these efforts to choose equally-sized random samples of each block of dialog, the fact that certain characters are given more time to speak will skew the results in ways that can’t be easily factored out. This caveat is seemingly supported by the fact that the results differ greatly when these methods of randomization and segmentation are changed. I will not pretend, then, that any of these results are definitive; rather, that they are useful as exploratory experiments only.

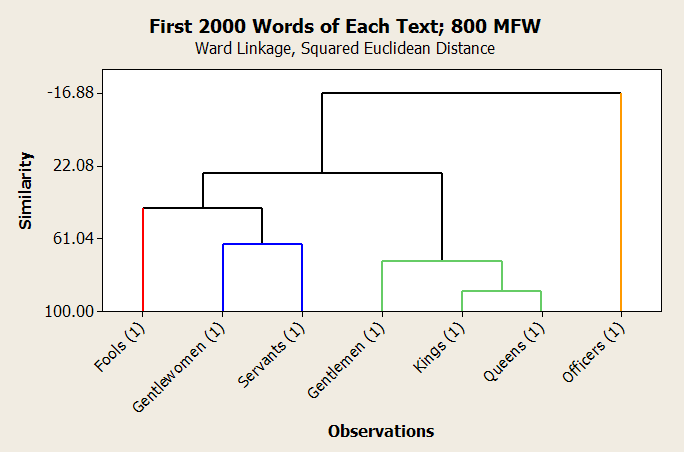

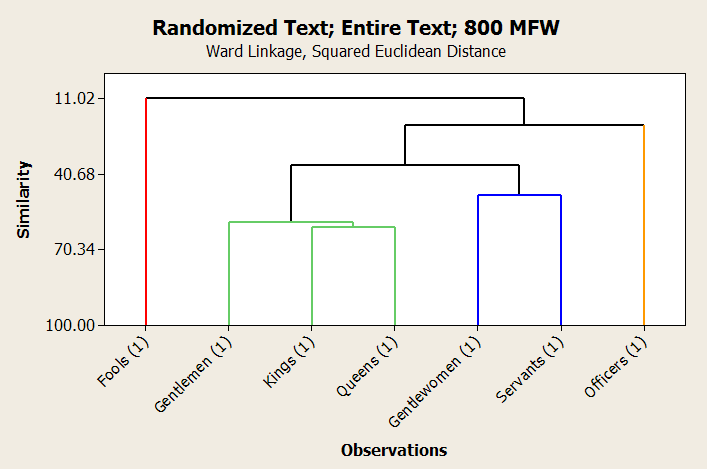

The above figure shows a dendrogram generated from a cluster observations analysis performed on the proportions of the 800 most frequently used words in each text, using the first 2000 words of each text. These results are very suggestive. Broadly, one could say that the leftmost group of six represents those employed at court, or in a royal, aristocratic setting, and the outlier, “officers,” represents those employed largely outside of court–members of the working class. Within the aristocratic group, there are two subgroups: a noble class and a servant class. That gentlewomen are paired with servants here is less of a statement about gender as it may seem–“gentlewomen” is a very sparse category, represented by only a few characters, all of whom seem to take a somewhat servile role by definition. (All but one of the gentlewomen are described as “attending on” a lady of some sort, such as Margaret, a “gentlewoman attending on Hero,” from Much Ado About Nothing.) As previously noted, however, the fact that this analysis only used the first non-randomized 2000-word segment from each text means that there’s a high likelihood that the larger categories only contain dialog from one or two plays. This can account for some, though not all, of this grouping.

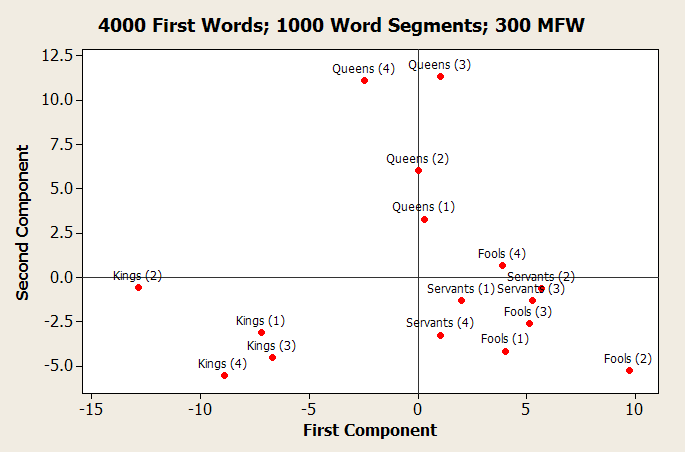

This figure represents an experiment conducted with the first 4000 words of each text, with each text broken into 1000-word segments. The texts were segmented like this in order to verify that the statical analysis was working–if Shakespeare’s queens sound roughly alike, then they should appear in similar areas of these charts. Since the “gentlewomen” category only contained around half of the required 4000 words, both the “gentlemen” and “gentlewomen” categories were eliminated. Here, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to generate two factors based on the similarity of the 300 most frequently used words in each text. Again, the results are very suggestive. On the whole, there are four main areas, in which the characters appear next to each other rather nicely. In the lower left quadrant, there are all the “kings” texts; in the upper center, there are all the “queens” texts, and in the lower right, there is an area where an area of “fools” texts collides with one of servants. One way to interpret these axes is that they might represent class and gender. The location of the queens texts seems to say that the y-axis is showing gendered stylistic differences. Similarly, the location of the fools suggests that the x-axis represents class standing, with the kings at the far end of the aristocratic spectrum, the servants in the middle, and the fools (and, it should be remembered, clowns of all sorts) on the opposite end. These same experiments, when conducted with 800 of the most frequently used words, show similar trends.

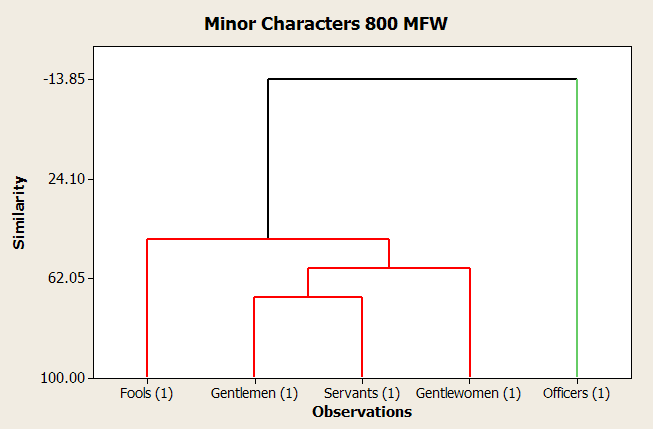

In an attempt to correct some of the skew caused by the differences in text length, a comparison was conducted between only the minor characters, all of whom have a similar amount of text. Although gentlemen are grouped closer to the servants than gentlewomen in this experiment, the remaining results, shown in Figure 4, are roughly the same as before. As one would expect, fools and officers, the two most anomalous groups according to their eccentricity and social standing, are the statistical outliers in this chart. Once again, however, the fools, owing perhaps to their standing within the court (though admittedly, this doesn’t apply to the clowns), are shown to be more similar to the gentlemen than are the officers.

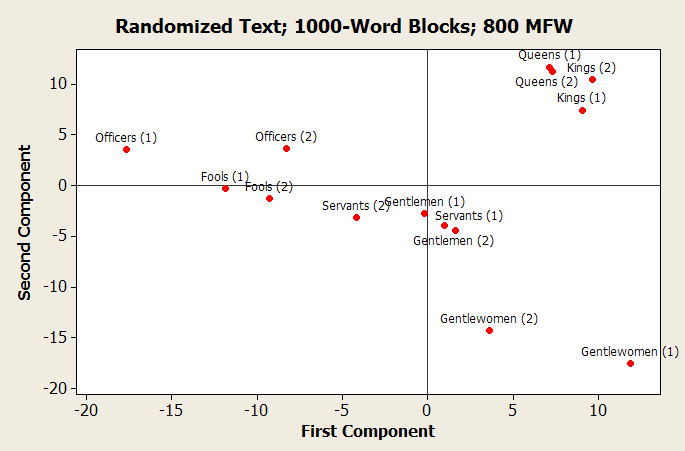

When the texts of these categories were randomized (filtered through

sort -R), a slightly different picture

emerged, as shown in the figure above. Again, the first 2000 words of

these texts were used, and then subdivided into 1000-word blocks, and

the first 800 most frequently words of the resulting set were analyzed.

On the whole, these parts appeared close to each other in the PCA score

plot. The categories, however, showed different affinities. This time,

kings and queens appeared much more similar. The outliers in this

projection are again officers, but this time, also gentlewomen. That

these two categories are the ones with the least text is perhaps

telling–maybe these results have been skewed in some way as a result of

that fact.

A tempting way to interpret this cluster diagram is as a sphere of influence. With the kings and queens in the upper-right quadrant (the relative position is computed, whereas the absolute position is somewhat arbitrary), they are surrounded by an entourage of characters with varying degrees of influence on them. The officers have the least influence on the kings and queens, followed by the fools and gentlewomen.

A more convincing picture might be found in a cluster analysis of the same data set, shown in the figure above. As before, the kings, queens, and gentlemen all group together, and the gentlewomen and the servants make a pair. This time, though, the fools and clowns are the outliers, followed by the officers at the opposite end. This result is identical between sets of 800 and 300 of the most frequently used words. This seems to confirm most of the interpretation previously suggested of the first figure.

These results all vary considerably. This variation has the double purpose of highlighting recurring motifs as potential candidates for evidence, and showing the instability of these analyses. What almost all of these experiments show is that the dialog of Shakespeare’s kings and queens is statistically dissimilar to the dialog of other characters. In most cases, the kings are queens are more like each other than any other characters. Most of the statistical divisions shown here take place along class lines. A more in-depth analysis of the language characteristic of these categories might help to shed some light on the exact nature of this division.

Distinctive Language Analysis

Next, the texts in these categories were compared with one another using David Hoover’s Full Spectrum Spreadsheet. This program identifies words that appear frequently in one text and rarely in another, and sorts them according to this ratio, in order to find words that are distinctive of each category. The resulting wordlists are indications of the language of their categories, insofar as they distinguish themselves from the categories with which they are being compared. The distinctive words of Shakespeare’s kings, for instance, when compared with that of fools, is very different from the words distinctive of kings when compared to queens. There are many place names and names of people in this former group, for instance–“Percy,” “Harry,” “Douglas,” “Wales,” “Westmoreland” and “Northumberland” all appear among the top 25 most distinctive words. These proper names appear much less frequently in comparison with other categories of characters. This would seem to suggest that the fools and clowns of Shakespeare speak more in abstractions than the kings. If one remembers the Fool’s song from King Lear, “Have more than thou showest, / Speak less than thou knowest,” this rings true.

When compared with officers, the words distinctive of kings are very different. The most distinctive word, somewhat unsurprisingly, is “love”–it would be an unusual soldier that would deliver a soliloquy about love, yet this would not be impossible for a Shakespearean king. Related words in this kings’ list include the sentimental terms “heart” at #17, “sweet” at #21, and “gentle” at #32–one would naturally not expect “sweet” and “gentle” to be words that a soldier would speak. There are also many kinship terms in this kings’ list–“son” at #7, “father” at #11, “cousin” at #43, and “wife” at #70. This suggests that the officers investigated here do not discuss their families–they are perhaps presented as if they have no families, as if duty were their only concern.

This sensitive image of Shakespeare’s kings changes when one compares them with queens. There, the words distinctive of kings are words of hierarchy–“lords” at #2, “Earl” at #10, “Duke” at #13; and militaristic words: “sword” at #23, “march” at #39, “war” at #47. There are still kinship terms, but they almost all denote male relatives: “brother” at #12, “uncle” at #20, and “father” at #40. In contrast, the kinship words that appear in the list characteristic of queens are all female: “wife” at #23, “daughter” at #24, and “woman” and “women” at #27 and #28. In fact, the list of most distinctive words in the kings’ dialog does not contain female pronouns. The word “she” appears high on the fools’ list (#4), the servants’ list (#9), and the queens’ list (#18), but does not appear in any of the kings’. The same is true for the word “her.” This phenomenon suggests that kings’ and queens’ domains are roughly gender-segregated into men’s and women’s spheres. Male royalty are predominantly concerned with other men, and female royalty are predominantly concerned with other women.

The words distinctive of kings, when compared with those of servants, are also telling. The three words most characteristic of kings in this context are “thou,” “thy” and “thee,” pronouns which denote familiarly or condescension. Since servants in Shakespeare don’t often have the luxury of condescension, the analogous words in the servants’ category are honorifics suggestive of deference–“master” (#1) “madam” (#4), and “mistress” (#8). The servants category features many such servile words when compared to the kings’ words: “please” (#3) and “sir” (#2) being the most frequent, and also “patience,” “service” “humbly,” and “honest” in the top 25. Interestingly, while the servants category features the plural “gods,” the kings category with which it is juxtaposed features the word “god” and the possessive “god’s.” This same phenomenon happens among the distinctive words of kings when compared with queens–“god” is ranked #5 for kings, and “gods” #24 for queens. Unfortunately, since the word “god” is rarely used to refer to the Christian diety, we cannot use these data as indicative of mono- or polytheistic settings.

Amazingly, none of the contractions that appear in these distinctive word lists are distinctive of kings. The word “‘tis" appears as distinctive of servants (#6), fools (#7), and queens (#51), but not kings. The fools’ wordlist contains “o’,” “we’ll,” “that’s,” and “‘a,” among others; the officers’ contains “what’s” and “let’s”; the queens’ list contains “he’s” and “there’s,” and the servants’ list contains “I’ll,” “that’s,” and “ta’en.” None of these words appear in any of the four kings’ lists. Are contractions like these spoken on a level of informality typically not seen in kings (but not, strangely, not unfamiliar to queens)? The OED does not help to answer this question, and neither does Blake’s dictionary of Shakespearean informal language (72, “Contractions”), so perhaps this is a matter better left to linguists or specialists in Renaissance language.

On the whole, categories’ distinctive words reflect the typical picture of those categories. “Ass” and “jest” appear in the fools’ (jesters’) list; “watch,” “prisoner” and “guard” appear in the officers’ list; and “crown” is a distinctive word for kings in three lists. In some cases, though, words appear as distinctive of unexpected categories. “Power” is not a word one would associate with gentlewomen, yet it is the third most distinctive word for that category, as compared with gentlemen. A concordance of the word “power” in the gentlewomen dialog was conducted to get to the root of this mystery:

grep power gentlewomen-dialog.txt > power.txt

while read p

do grep -B 20 "$p" *.xml

done < power.txtThe first of these lines searches gentlewomen-dialog.txt for the word “power,” and

outputs the results to a file called power.txt; the subsequent lines read the lines

of power.txt individually and search all

the plays (all the XML files) for the lines in the file, giving 20 lines

of context (-B 20) so that the speaker may

be identified. The output from these commands reveals that the speaker

of this word “power” is, in all cases, Helena from All’s Well That

Ends Well–a passionate character, indeed.

Other unexpected words from these lists include “love” at the top of the king’s list. This isn’t a word one would expect to be characteristic of Shakespeare’s kings, but when compared with officers, it is their most distinctive word. Although “blood” is a characteristic word for kings in three lists (#18, v. fools; #3, v. gentlemen; #11, v. servants), it also appears as the nineteenth most distinctive word of gentlewomen. Again, a concordance using the BASH commands above reveals that “blood” is also, in all three cases, Helena’s word, a fact which remains consistent with her fiery nature.

Also of note in these wordlists is the fact that the word “nay,” while it appears high on the lists of fools, queens, servants, and gentlemen, doesn’t appear at all in the list of distinctive kings’ words. Although a concordance of the dialog shows that the word appears several times among Shakespeare’s kings, the fact that this word appears more frequently among the other groups of characters seems to suggest that the kings are relatively affirmative, whereas the others could rightly be called “naysayers.” It is tempting to take this interpretation further, but the presence or absence of such a versatile word could not with certainty lead to a clear reading.

Conclusion

Here we have seen that class structure in Shakespeare, although by no means unified and unambiguous, can be revealed to some extent by a statistical comparison of categories of dialog. Similarly, gender differences–those between kings and queens, for instance–can also be shown using PCA analysis. Many of the distinctive words found with the Full Spectrum Spreadsheet are unsurprising for their categories, yet many unusual or surprising words also appear, a phenomenon which leads to insights about particular anomalous characters. A more qualitative inquiry might examine in greater detail the anomalies found in these lists, and contextualize them more among the personalities of their particular characters.

Although this investigation is not traditionally conclusive, it has raised some questions which might lead to further study. The limitations of such macro-oriented work as this, which deals with dialog on the level of Shakespeare’s entire dramatic oeuvre, also present opportunities for more minute, focused work. One such study, for instance, might separate fools from clowns, and compare the language used in both. Another might compare the speech of officers with that of soldiers, or that of princes with that of kings. Many of the observations of language mentioned here–such as the use of contractions among non-royal speakers–deserve further inquiry.

Bibliography

Blake, N F. Shakespeare’s Non-Standard English: A Dictionary of His Informal Language. London: Thoemmes Continuum, 2004. Ebrary. Accessed 21 May 2013.

Wells, Stanley. “Clown.” A Dictionary of Shakespeare. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998. Oxford Reference. 2003. Accessed 21 May. 2013.

Presentation Slides

Slides from this paper’s presentation at the workshop Computer-Based Analysis of Drama, at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, in March 2015.