Posted 2015-03-02

In an 1873 review in the Galaxy, Henry James criticizes George Eliot’s Middlemarch as he might a painting: “it abounds in fine shades, but it lacks, we think, the great dramatic chiaroscuro” (579). Although James is using the term metaphorically, to denote sweeping emotions and narrative flux, the same could be said of the visual mise-en-scène of the novel. The presence of literal light and darkness in a novel’s descriptive tableaux lays a visual foundation that often projects to the greater narrative structure. Imagery of intense light and stark shadows is correlated with similarly tumultuous brush strokes in the plot—chiaroscuro functions both poetically and narratologically. While this phenomenon is subtle in a novel like Middlemarch, other Victorian novels, especially Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, exemplify this shadow play. The following study synthesizes quantitative and qualitative methods to compare these two novels, to show how these writers employ optical effects to frame their theatrical dynamics. Where Dickens uses chiaroscuro to heighten dramatic intensity, Eliot uses it as a preliminary artistic maneuver towards a more deliberately subtle mezzotint.

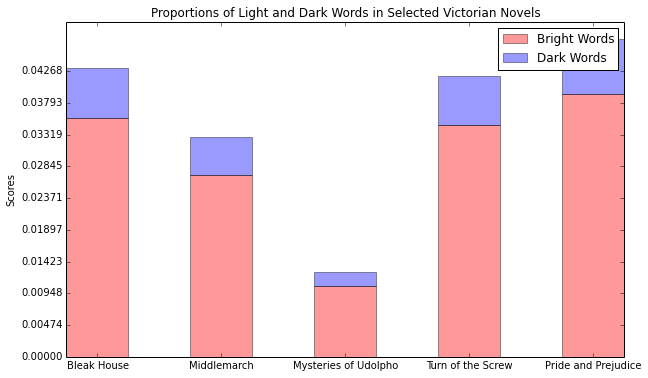

A computational analysis of light and dark words in these novels suggests, to whatever small degree these tropes may be quantified, Henry James might have been right that Middlemarch lacks “chiaroscuro,” at least in comparison to a small number of other Victorian novels. To test this claim, a wordlist of hyponym lemmas was generated with the Princeton Wordnet, using the seed concepts “light” and “dark.” The wordlist was curated to remove irrelvant word senses, and the novels were then analyzed for the presence of these words, using the Python Natural Langauge Processing Toolkit. Adjusted for the total number of words in each novel, the combined score for light and dark words in Middlemarch was 3.28, while it was 4.31 for Bleak House. Middlemarch also scored lower than Henry James’s Turn of the Screw (4.18), a decidedly dark gothic novella, and even scored lower than Jane Austen’s largely domestic novel of manners, Pride and Prejudice, which exhibited a surprisingly high score of 4.74 (see Figure 1).

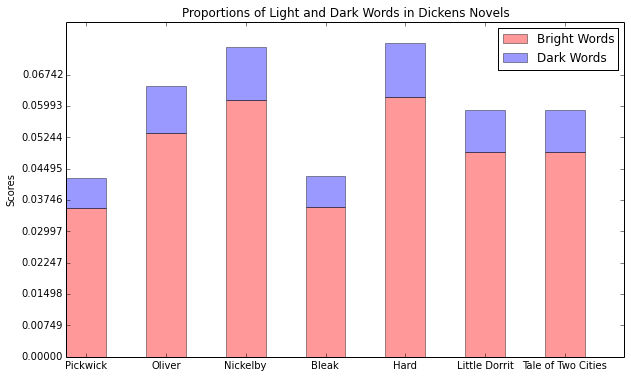

Another surprising finding of this analysis was that Bleak House scored much lower for light and dark words than other Dickens works, despite the fact that it is widely regarded as the first of his “dark novels” (q.v. Stevenson). It scores lower than Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickelby, Hard Times, Little Dorrit, and A Tale of Two Cities—all tested novels except The Pickwick Papers (see Figure 2). Of course, a simple word search cannot definitevely reveal the full breadth of lexical expression that convey a mood; a dark or light scene might be described more than adequately without ever using the words “dark” or “light,” or any of their hyponyms. One would expect the numbers of these words to be unusually high, for instance, in Ann Radcliffe’s archetypal gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, but the score is a very low 1.27. One must conclude that a more sophisticated computational model is needed here. In the meantime, a qualitative textual analysis will help to fill that need.

Very broadly, the traditional associations of light and darkness are those of good and evil, respectively. Norman Friedman’s 1975 treatment of “Sun and Shadow” in Bleak House, for instance, turns almost immediately into a discussion of morality and “the problem of evil” (363). An interpretation of chiaroscuro that stops at that level, however, misses much—light is also associated with knowledge and science, an association perhaps best represented as the periods that have been called the Enlightenment and the Dark Ages. Closely related are temporal connotations: light, especially gas light, in the Victorian imagination, could be said to be associated with the future and technological progress, whereas the past is increasingly shrouded in darkness. There is also a racial and social connotation, exemplified, for instance, in the title of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which adds a further dimension to this imagery. The multiplicity of meanings associated with chiaroscuro allows for an exploration of certain patterns of ambiguity, such as that in the binaries of the visual/tactile, emotional/epistemological, and technological/ontological.

The material conditions of lighting in the mid-19th century helped to shape their literary manifestations. Matthew Luckiesh describes this period as a transition between “mere” light and “more” light: “Until the middle of the nineteenth century mere light was available … Gradually mere light grew to more light and in the dawn of the twentieth century adequate light became available” (ix). It is even more true now that “In the present age of abundant artificial light, with its manifold light-sources … mankind does not realize the importance of this comfort” (5). Catherine LeGouis notes that “By mid-century, technological changes had brought about a different way of looking at reality using these new means of lighting, deeply affecting the realists’ use of the light/dark opposition” (424). Although LeGouis is primarily writing about Zola’s Paris (and although the shadows of Paris do appear in Bleak House), the same may be said of much of England. Bright gas streetlights had been installed throughout London in the early 19th century (Pool 198). George Sala, writing in Dickens’s Household Words, declares that “Not a bolt or bar, not a lock or fastening, not a household night-wanderer, not a homeless dog, shall escape that searching ray of light which the gas shall lend him, to see and to know” (341). The juxtaposition here, of “to see” and “to know,” is more than a reworking of the cliché “seeing is believing”—it associates visual experience with knowledge, hinting at an epistemological theory dependent on the experience of light.

Domestic lighting in early Victorian England would not have been nearly as bright as these gas lights, especially for the working class. Instead, candlelight or even rushlight would have been more common (Pool 198-9). The entry in the Imperial Dictionary of the English Language for “rush-light” calls it “any weak flickering light,” and even cites Dickens’s Pickwick Papers: “smoking and staring at the rush-light” (Ogilve 747). Dickens’s use of light, however, is more than just descriptive; it leaps out of the fireplaces and casts shadows on everything in the room, even (or perhaps especially) the psychological states of the characters.

John Ruskin, in a section of Modern Painters titled “The Truth of Chiaroscuro,” argues that “shadows are in reality, when the sun is shining, the most conspicuous thing in a landscape, next to the highest lights. All forms are understood and explained chiefly by their agency” (175). Later, in an 1863 letter to his father, Ruskin writes about his favorite scenes from Charles Dickens, all of which involve dramatic natural lighting: “The storm in which Steerforth is wrecked, in Copperfield; the sunset before Tigg is murdered by Jonas Chuzzlewit; and the French road from Dijon in Dombey and Son … are quite unrivalled in their way” (215). Perhaps what he finds appealing about Dickens is the same quality he celebrates in Turner. Although Ruskin does not mention Bleak House specifically, what he says of Copperfield certainly applies here.

Dickens has been rightly called “the most intensely visual of Victorian writers” (Andrews 97). In fact, he began his career as a novelist with images of light and darkness. The first sentence of his first novel begins:

The first ray of light which illuminates the gloom, and converts into a dazzling brilliancy that obscurity in which the earlier history of the public career of the immortal Pickwick would appear to be involved, is derived from the perusal of the following entry in the Transactions of the Pickwick Club, … (P 1)

The sentence continues for many more lines. The verbosity here, and also its intense, poetic light imagery, may have been what led critic Garrett Stewart to claim, of this sentence, that “After Dickens, no one could write that way again and be taken seriously” (136). The contrast between “gloom” and “dazzling brilliancy” is striking, especially for the opening passage of a novel. It is further striking to discover that this light is not, as one would imagine, a description of a landscape, but rather the figurative light of knowledge that illuminates Pickwick’s “public career” for the readers. The light imagery, therefore, has a threefold purpose: its literal associations paint a dramatic, Turnerian picture; its figurative meaning inaugurates an epistemological theme, and provides narrative tension by withholding information; and its association with the public places the light/dark dichotomy in dialog with the public/private.

This style is further intensified with Bleak House, which is often called the first of Dickens’s “dark” novels. Norman Page explains this term:

[Dickens] was no longer a young man, recently and happily married, with the world at his feet, but was middle-aged, unhappy in his personal life, and in deteriorated health. Beyond all this, though, the pessimism also seems a reaction to the problems of the age … For this reason the later novels have often been referred to as Dickens’s ‘dark’ novels … (2)

Here, “dark” is mostly being used to mean “pessimistic” or “unhappy,” but there is also the more literal connotation of “lacking light.” Dickens’s later novels deal with unpleasant social realities (social “darkness”), but also with darkness itself. This ambiguity is one that locates unhappiness in the visual realm, one that conflates emotion with visual experience.

The major settings of Bleak House—the High Court, Chesney Wold, Tom-all-Alone’s, and Bleak House itself—are described (one could nearly say “painted”) in terms of light and darkness. The High Court of Chancery, Chesney Wold, and Tom-all-Alone’s are dark; Bleak House, despite its name, is bright. The fog and darkness of the Court directly parallels a psychological darkness in the solicitors. The court itself is described as “dim, with wasting candles,” with “fog hang[ing] heavy … windows admit[ting] no light of day” (6). Similarly, the members of the bar are “mistily engaged in one of the ten thousand stages of an endless cause.” It is perhaps because of the fog and darkness that they are “tripping one another up on slippery precedents” and “groping knee-deep in technicalities.” In contrast, we are first introduced to Bleak House as “a light sparkling on the top of a hill” that becomes “a gush of light from the opened door” (59). Esther’s “first impressions” of the house remark about “its illuminated windows, softened here and there by shadows of curtains, shining out upon the starlight night” and its “light, and warmth, and comfort” (64). Tom-all-Alone’s, predictably, is “black,” and every so often a house collapses in a “cloud of dust” (197). The first time we see Mr. Krook’s “Rag and Bottle Warehouse,” it is “foggy and dark,” and whatever light there is, is “intercepted” by the shop; Mr. Tulkinghorn’s office is lit by “two candles in old-fashioned silver candlesticks that give a very insufficient light” (119).

The characters, too, are sketched with chiaroscuro. Esther Summerson’s surname, as Friedman points out, resonates with “summer sun” (366). When she is reconciled with Mr. Jarndyce, which is to say, relieved of her promise to marry him, he speaks “radiantly and beneficently, like the sunshine” (752). Conversely, Richard and Ada, when they come to terms with their inability to marry each other, are seen to pass from “the adjoining room, on which the sun was shining,” continue “lightly through the sunlight,” and finally disappear ominously “into the shadow” (163). The narrator laments, “It was only a burst of light that had been so radiant. The room darkened as they went out, and the sun was clouded over.”

The description of Sir Leicester’s clothes (ironically, in a chapter called “In Fashion”) is similarly monochromatic: “One peculiarity of his black clothes and of his black stockings, be they silk or worsted, is that they never shine. Mute, close, irresponsive to any glancing light, his dress is like himself” (14). Like his clothes, one might say that Sir Leicester is “unreflective,” both in the sense that he is lackluster, and in the sense that he doesn’t seem as thoughtful as the other figures in the novel. Here, light is revealed to be something more than an inherent quality—it is either reflected or absorbed by certain characters. Esther, in contrast, says that she “had never worn a black frock” (18).

Fire, as a source of light and shadow, is used heavily throughout Bleak House. Patricia Marks, writing about Barnaby Rudge, argues that fire, as man-made light “may be used to fulfill its original creative function or may be perverted into a destructive force,” and that “a domestic fire serves the function of providential light. At the Maypole, for example, the central fireplace not only vanquishes darkness but also, like the sun, causes reflections in everything that surrounds it” (74). When Mr. Tulkinghorn goes to find the dead Nemo, he is met with darkness: “He comes to the dark door … He knocks, receives no answer, opens it, and accidentally extinguishes his candle in doing so. The air of the room is almost bad enough to have extinguished it if he had not” (124). Dickens made a point to show that this candle did not extinguish itself by accident—that way, it is more obvious as an omen of the soon-to-be-discovered death. When Krook tries to light it later, he discovers that, in a similar image, “the dying ashes have no light to spare” (125).

Simultaneously, Mr. Krook’s spontaneous combustion might be read as an example of Mark’s “destructive force” which “serves the function of providential light” by “vanquishing” the “darkness” represented by Mr. Krook. The first time we meet him, his breath is, by way of subtle foreshadowing, “issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within” (49). Once he becomes a pile of ashes, the narrator insinuates that he was but one of many “lord chancellors” who make “false pretences” and do “injustice,” and that, as a result, he met with the same fate as they did—“Spontaneous Combustion” (403). Dickens’s implication, of course, is that all of these “lord chancellors,” if they are not already dead, are dying slowly, from the inside out, of some sort of moral decay. The fire, then, acts as a kind of judge for this immorality, separating the light from the shadow. What Marks says about Barnaby Rudge, therefore, that it “presents … a history of the cosmic alternation between life and death as represented by light and darkness” is not entirely true of Bleak House (76). Darkness is not always associated with death—during Jo’s death, for instance, “the light is come upon the dark benighted way” (572).

Darkness and shadow don’t always have a negative connotation in Bleak House. An early scene has Ada sitting at a piano, with Richard standing besider her. On the wall, “their shadows blended together,” foreshadowing, so to speak, their blended fates (68). Donald Ericksen compares this subtle note to similar visual themes in Victorian narrative paintings: “The reader is expected to puzzle out the meaning of the scene in terms of the present and the future, as Esther’s response leads us to do” (38). In Middlemarch there is a strikingly similar scene, which describes Dorothea and hints at her growing sexual awareness:

…there was nothing of an ascetic’s expression in her bright full eyes, as she looked before her, not consciously seeing, but absorbing into the intensity of her mood, the solemn glory of the afternoon with its long swathes of light between the far-off rows of limes, whose shadows touched each other. (18)

Hablot Browne’s Illustrations for Bleak House extend this textual theme. There are ten “dark plate” illustrations, in particular, that accompany dark moods in the text. As Ericksen explains, “The illustrator created these dark plates by first making fine machine-ruled lines through the etching ground and then later applying the acid and stopping-out processes. In this manner an infinite range of tones could be produced” (37). This evening-out of the tone also allowed the background elements to take on more visual importance (Harvey 152). The lack of human figures in many of them further accentuates the background. In the plate titled “Tom-all-Alone’s,” for instance, the lack of characters draws attention to the architecture and to the poverty of the street.

Perhaps the most intense chiaroscuro among these illustrations is the plate titled “A New Meaning in the Roman” (586). The title is a reference to the pointing Roman figure of Allegory painted on the ceiling, who is now pointing to the blood stain on the floor. The light streaming through the window, which also points directly to the blood stain, suggests a selective attention—an epistemology of the apartment. Its juxtaposition with the pointing finger suggests that the light is a kind of accusatory vector, as well. In this sense, the beam of light takes on the function previously held by the fire: that of divine judgment. As Richard Stein interprets it, “emphasis falls on contrasted signifying modes: allegory has been socialized, traditional iconography supplanted by a more diffuse and complex visuality” (183). Indeed, the repetition of forms here in this illustration suggests a proliferation of allegory.

The text and illustration of this scene diverge. In the text, the narrator reprises the ominous dark imagery in saying that “no light is admitted into the darkened chamber” (585), whereas sunlight appears to be coming through the window in the illustration. Whereas the candles in the illustration are lit, they are extinguished in the text: “He [Allegory] is pointing at a table, with a bottle (nearly full of wine) and a glass upon it, and two candles that were blown out suddenly, soon after being lighted.” This image recalls the earlier extinguished candle, also associated with Tulkinghorn.

“Consecrated Ground,” another dark plate, depicts a graveyard illuminated with dramatic rays of light from the streetlamps. As in “A New Meaning,” this illustration features a pointing figure, and the pointing motion is mirrored by the action of the light. The ray of light here, due to the way it falls around the corners of gravestone, is shaped like a pointing hand, which gives Joe’s pointing hand a circumstantial halo. Stein argues that “where Jo points through the churchyard gate to Nemo’s grave, the boy’s gesture directs our eyes past the edge of the image, toward an invisible world of death that resists imaging and interpretation” (179). Lady Dedlock’s face is turned away, heightening her perceived anonymity here, to both Jo and to the reader.

Some of the most explicit acknowledgment of light and shadow comes from two illustrations named, appropriately, “Light” and “Shadow.” The subject matter of these plates is telling: “Light” is a bright domestic scene; “Shadow” is dark and ominous. The passage “Light” illustrates is taken from the chapter titled “Enlightened,” most likely a reference to the scene where Esther learns of Richard and Ada’s marriage:

…[Ada] rose, put off her bonnet, kneeled down beside him with her golden hair falling like sunlight on his head … “Esther, dear,” she said very quietly, “I am not going home again.”

A light shone in upon me all at once.

“Never any more. I am going to stay with my dear husband. We have been married above two months.” (613)

Here, light imagery is used to symbolize knowledge, as it does in the name of the Enlightenment era. This association is supported by, among other elements, the centrality of the bookcase in the illustration and the papers scattered throughout this apartment. The knowledge of Ada and Richard’s marriage is perhaps that which gives these two characters the halo-like glow which forms the lightest area of the illustration. The darkest area of the illustration, in keeping with this symbolism, is the area behind Esther, away from which she appears to be moving. In fact, the light appears to be coming from the direction of the viewer. The twin circular areas of light would almost seem to indicate a pair of eyes, as if somehow acknowledging the presence of the viewer/reader. Since the strongest light surrounds Ada and Richard, there is also the symbolic connection between light and romantic love, a symbolism we will encounter again with Middlemarch.

The companion illustration, “Shadow,” depicts a lone Lady Dedlock, ascending a dark staircase after having encountered Mr. Bucket. She is eying, in passing, a poster, which in the illustration reads “Murder! £100 Reward!”. The passage reads:

She scarcely makes a stop, and sweeps up-stairs alone. Mr. Bucket, moving towards the staircase-foot, watches her as she goes up the steps the old man came down to his grave; past murderous group of statuary, repeated with their shadowy weapons on the wall; past the printed bill, which she looks at going by; out of view. (635)

This is a remarkably visual passage, putting the reader in Mr. Bucket’s place as he watches his suspect Lady Dedlock. “Murder,” in various forms, is “repeated” several times in the illustration: in the suspected Lady Dedlock, in the poster, and in the statuary. Michael Steig points out that this statuary “appears to be Abraham and Isaac at the point when Abraham is about to sacrifice his son,” and cites Ronald Paulson’s interpretation that this might “allude to the contrast between God’s and man’s justice” (153). With that in mind, the shadow that “repeats” this image might be read as another instance of light acting as a divine judge.

George Eliot’s Middlemarch, in keeping with Henry James’s critique, features light and dark symbolism to a somewhat lesser degree. It is not, however, completely absent, and the way in which she uses these symbols is very different from in Bleak House. The phrase “lights and shadows” appears five times in the text, and each time accumulates meaning. The first usage is to contrast Bulstrode’s stringently sanctimonious chiaroscuro with the mezzotint moral gradations of those he hypocritically judges:

This was not the first time that Mr. Bulstrode had begun by admonishing Mr. Vincy, and had ended by seeing a very unsatisfactory reflection of himself in the coarse unflattering mirror which that manufacturer’s mind presented to the subtler lights and shadows of his fellow-men … (84)

The second instance also appears after a quarrel, this time between Dorothea and Casaubon. Once again, the “lights and shadows” mirror a discrepancy between imagination and reality. In the above passage, it is Bulstrode’s haughty pietism; in the passage below, it is the contrast between Dorothea’s imaginary idealized marriage and its realities:

Dorothea was crying, and if she had been required to state the cause, she could only have done so in some such general words as I have already used: to have been driven to be more particular would have been like trying to give a history of the lights and shadows, for that new real future which was replacing the imaginary drew its material from the endless minutiae by which her view of Mr. Casaubon and her wifely relation, now that she was married to him, was gradually changing with the secret motion of a watch-hand from what it had been in her maiden dream. (124)

The third scene with this phrase comes directly before chapter XXII, when Dorothea and Will have one of their first flirtatious conversations in Rome.

We are all of us born in moral stupidity, taking the world as an udder to feed our supreme selves: Dorothea had early begun to emerge from that stupidity, but yet it had been easier to her to imagine how she would devote herself to Mr. Casaubon, and become wise and strong in his strength and wisdom, than to conceive with that distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling—an idea wrought back to the directness of sense, like the solidity of objects—that he had an equivalent centre of self, whence the lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference. (135)

Here the contrast between “lights and shadow” seems to parallel the contrast between Dorothea’s “devotion” and her “feeling”—what we might assume is her budding sexual awakening. This chiaroscuro still reflects the imagination/reality duality, but it has taken on a slightly new form—the imagined realm now parallels the world of social responsibility (to Dorothea’s marriage, for instance), while the real parallels that of passion, of “directness of sense, like the solidity of objects.”

Next, “lights and shadow” are associated with Mr. Farebrother: “Mr. Farebrother came up the orchard walk, dividing the bright August lights and shadows with the tufted grass and the apple-tree boughs” (251). Although this scene is more of a landscape painting than a psychological treatise, there are still the implications of an impending drama. In the following scene, Farebrother delivers the Garths the news that Fred Vincy is leaving town. This is the first of many times he will act as an intermediary—fulfilling his role as clergyman by dividing, in a sense, the “lights and shadows.”

A more subtle scene involving light takes place in the Roman gallery. Here again, light is associated with sensuality. It is necessary to quote this passage at length:

… the two figures passed lightly along by the Meleager, towards the hall where the reclining Ariadne, then called the Cleopatra, lies in the marble voluptuousness of her beauty, the drapery folding around her with a petal-like ease and tenderness. They were just in time to see another figure standing against a pedestal near the reclining marble: a breathing blooming girl, whose form, not shamed by the Ariadne, was clad in Quakerish gray drapery; her long cloak, fastened at the neck, was thrown backward from her arms, and one beautiful ungloved hand pillowed her cheek, pushing somewhat backward the white beaver bonnet which made a sort of halo to her face around the simply braided dark-brown hair. She was not looking at the sculpture, probably not thinking of it: her large eyes were fixed dreamily on a streak of sunlight which fell across the floor. But she became conscious of the two strangers who suddenly paused as if to contemplate the Cleopatra … (121)

This passage exemplifies the tension between the Dorothea’s “Quarkerish” qualities and her “breathing,” “blooming” nature, here intensified by the juxtaposition with the “volutuousness” of the statue. This dichotomy is superimposed upon that of the statue, which also has a double identity. It is now known as Ariadne, whose name literally means “most holy,” and would therefore be associated with Dorothea’s religious personality, yet it was then known as Cleopatra, one of the most sexually charged characters of antiquity. While Ariadne is sleeping in marble, Dorothea is daydreaming, with her hand as her pillow. Light plays a major role in this scene, as that which gives Dorothea her “halo,” and that which hypnotizes her. Light, as the medium through which all vision takes place, is here the mode through which Will’s gaze fixes itself on Dorothea. That artistic gaze is then that which divides the light from the dark, and thus the social from the primal, the responsible from the passionate. Where Dickens uses light and darkness to intensify divine moral judgments of his characters, Eliot uses it to liberate them from these divine judgments.

In closing, it might be useful to respond to Henry James’s criticism with that of his contemporaries. While it may be true that Middlemarch lacks a certain chiaroscuro, perhaps that is its literary strength. To quote Ruskin again, “It is the constant habit of nature to use both her highest lights and deepest shadows in exceedingly small quantity … thus reducing the whole mass of her picture to a delicate middle tint” (180). This “delicate middle tint” might be a good way of describing Middlemarch.

Works Cited

Andrews, Malcolm. “Illustrations.” A Companion to Charles Dickens. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 97-125. Print.

Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

—. Bleak House. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1977. Print.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. Print.

Ericksen, Donald H. “Bleak House and Victorian Art and Illustration: Charles Dickens’s Visual Narrative Style.” The Journal of Narrative Technique 13.1 (2012): 31-46. Print.

Friedman, Norman. “The Shadow and the Sun: Archetypes in Bleak House.” Form and Meaning in Fiction. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1975. Print.

James, Henry. “George Eliot’s Middlemarch.” Middlemarch. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. 578-581. Print.

LeGouis, Catherine. “Optics and Rhetoric: Images of Light in Zola.” Romanic Review 84.4 (1993): 423-436. Print.

Luckiesh, Matthew. Artificial Light: Its Influence upon Civilization. The Century Co., 1920. Web. 13 May 2012.

Marks, Patricia. “Light and Dark Imagery in Barnaby Rudge.” Dickens Studies Newsletter 9.6 (1976): 73-76. Print.

Ogilvie, John. The Imperial Dictionary of the English Language. Blackie & Son, 1884. Web. 16 May 2012.

Pool, Daniel. What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew: From Fox Hunting to Whist: the Facts of Daily Life in Nineteenth-century England. Simon & Schuster, 1994. Web. 16 May 2012.

Ruskin, John. “From a Letter.” Charles Dickens Critical Assessments. Ed. Michael Hollington. Mountfield, UK: Helm Information, 1995. Print.

—. The Works of John Ruskin: Modern Painters, V.1. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1890. Print.

Sala, George. “The Secrets of the Gas.” Household Words 1854: 338-345. Web.

Stein, Richard L. “Bleak House and Illustration: Learning to Look.”

Approaches to Teaching Dickens’s Bleak House. New York: Modern Language Association, 2008. Print.

—. “Dickens and Illustration.” Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Print.

Stevenson, Lionel. “Dickens’s Dark Novels, 1851-1857.” The Sewanee Review 51.3 (1943). Web. 23 November 2014.

Stewart, Garrett. “Dickens and Language.” Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 136-151. Print.