Posted 2014-10-21

Virginia Woolf’s experimental novel The Waves is structured as a series of dialogues and monologues by six characters. Some of these speeches are as short as a line, but most are between a few paragraphs and a chapter in length. Their extremely regular structure takes this form:

‘I see a ring,’ said Bernard, ‘hanging above me. It quivers and hangs in a loop of light.’ (Woolf 9)

There is a short phrase, an attribution with the word “said,” and a continuation of the speech–this is true of all the speech in the novel. This regularity makes this novel an unusually good subject for computational study, since the text can so easily be extracted—see Stephen Ramsay’s tf/idf experiment, and Chris Forster’s subsequent blog post, wherein he suggests a possible regular expression to capture dialogue. Additionally, the fact that there are three male characters and three female characters make this an interesting study for the investigation of gendered speech, at least as it appears in Woolf.

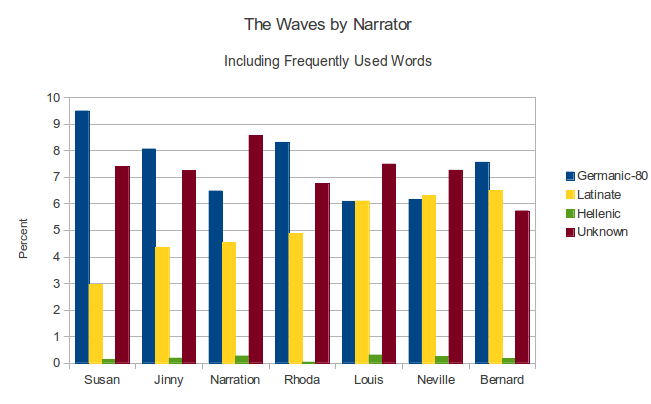

For this experiment, text files containing each of the characters’ total speech were fed through the Macro-Etymological Analyzer. As the figure below shows, the macro-etymologies of the characters’ speech are distinct, and separate by gender, with the male characters showing the highest proportions of Latinate words, and the female characters showing the lowest.

Bernard and Neville are the two university-educated characters, and the ones with the highest proportions of Latinate words. Bernard identifies with Shakespeare and is, according to Fogel, “a clear surrogate for Virginia Woolf herself” (157, quoted in Hussey, 25). Neville “anticipates becoming a classical scholar, exploring the writing of Virgil, Lucretius and Catallus” (Hussey 181-2). Early in the novel, Neville imagines entering the library where he “shall explore the exactitude of the Latin language” (31). That exactitude is invoked by Bernard later–during one of his conversations with Neville, he praises him thus:

you wish to be a poet; and you wish to be a lover. But the splendid clarity of your intelligence, and the remorseless honesty of your intellect (these Latin words I owe you; these qualities of yours make me shift a little uneasily and see the faded patches, the thin strands in my own equipment) bring you to a halt. (85)

The “Latin words” to which Bernard refers are “splendid,” “clarity,” “intelligence,” and “remorseless,” all words descended from Latin which entered English through French. Later, Bernard describes Percival as one who thinks with “magnificent equanimity” (243). In parentheses, he justifies his own florid word choice here by saying “Latin words come naturally.” Is Woolf implying that, due to social circumstances, perhaps Latin words do not come as “naturally” to the female characters?

In contrast to Bernard and Neville, Jinny is “sensual, alert to vivid color and to the power of her own body to attract men” (Hussey 131). Susan is a “representation of the maternal ‘instinct.’ … closely identified with the natural world. She marries a farmer, lives in the country, and is fiercely protective of her children” (280). These are qualities typically associated with Anglo-Saxon words—visceral, sensual words; kinship terms, rural settings.

In Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” she imagines a female Shakespeare, Shakespeare’s sister Judith. Woolf argues that Judith Shakespeare couldn’t have written her brother William’s works, not from lack of talent, but from lack of opportunities–“rooms of one’s own” for Elizabethan women writers during this period. “She had no chance of learning grammar and logic,” Woolf contends, “let alone of reading Horace and Virgil. She picked up a book now and then, one of her brother’s perhaps, and read a few pages. But then her parents came in and told her to mend the stockings or mind the stew and not moon about with books and papers” (47). Therefore, one imagines that Judith Shakespeare, like the female characters in The Waves, would have used fewer Latinate words than her male counterparts.

Works Cited

Hussey, Mark. Virginia Woolf A to Z. New York: Facts on File, 1995. Print.

Ramsay, Stephen. “Algorithmic Criticism.” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. Web. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s One. New York: Harcourt, 1929. Print.

—. The Waves. New York: Harcourt, 1931. Print.

Note

This post is an adapted and expanded excerpt from my 2013 Master’s thesis, “Macro-Etymological Textual Analysis: an Application of Language History to Literary Criticism.” The program described herein is the web app created for these experiments, the Macro-Etymological Analyzer. Read more about the program and related experiments in my introductory post, “Introducing the Macro-Etymological Analyzer.”