Posted 2014-09-14

Walt Whitman, in addition to being a poet, was somewhat of an amateur etymologist. He calls the English language “an enormous treasure-house, or range of treasure houses, arsenals, granary, chock full with so many contributions … from Spaniards, Italians and the French” (quoted in LeMaster, 226). In the preface to the first edition of Leaves of Grass, he summarizes the history of English word borrowing: “On the tough stock of a race who through all change of circumstance was never without the idea of political liberty … [the English language] has attracted the terms of daintier and gayer and subtler and more elegant tongues” (PW, II, 456-57, quoted in Warren, 34). Here, the “tough stock” is Anglo-Saxon, and the “more elegant tongues” are French, Latin, and Greek (35). Elsewhere, he credits French as the power that “free[d] the nascent English speech from those useless and cumbersome forms with which the Anglo-Saxon was overloaded (Rambles, 273, quoted in Warren, 45).

In his poems, Whitman uses foreign words and expressions liberally, and a few critics have noted that his use of loanwords increases with every revision of his magnum opus Leaves of Grass (LeMaster 227). French loanwords, many of which he may have picked up from his travels in Louisiana, were some of his favorites. Whitman himself comments on his own use of French words in an article he published in the Brooklyn Times in the 1850s. In this article, he gives a long list of French words, calling them “a few Foreign Words, mostly French, put down suggestively” (Asselineau 368, n143). He continues, “some of these are tip-top words, much needed in English.” Indeed, many of these words, such as “insouciance,” “cache,” and “ennui,” have now entered the English langauge, but others, such as the titularly appropriate “feuillage,” have not. As LeMaster and Kummings note, Whitman anglicizes some French words, dropping some of the accents, and uses phonetic or creative spellings for others, rendering “rondeur” as “rondure,” for instance, a spelling which recalls “verdure” (227). While some of these French loanwords are probably malopropisms—“resumé” in “Night on the Prairies,” for instance (LeMaster 228), others bring new levels of meaning to the poems. One of these orthographic inventions, the title of his poem “Respondez!” is especially interesting. If we do not dismiss this as an archaic or erroneous spelling of the French “repondez,” we might read it as a mixture of the French word with the English “respond,” which itself is derived from the Old French “respondere.” The word is both more English-sounding (to the anglophone ear) than its modern French equivalent, and more archaic in tone than its modern equivalents in either language—the word straddles two languages, and five hundred years of language history.

Another interesting case is Whitman’s use of the French word amie, which appears twice in the 1855 “Song of Myself.” He uses the feminine form of the word, even though he uses it to refer to a man: “Picking out one here that shall be my amie, / Choosing to go with him on brotherly terms” (quoted in Warren, 700-1). Furthermore, as Warren points out, Whitman is well aware of the gendered forms of this word, for he defines both forms in his essay “America’s Mightiest Inheritance.” The definition he gives for both is “Dear Friend.” Here again we have an instance of linguistic divergence—in French, “ami(e)” simply means “friend”; Whitman has imported the word and given it a more specialized meaning.

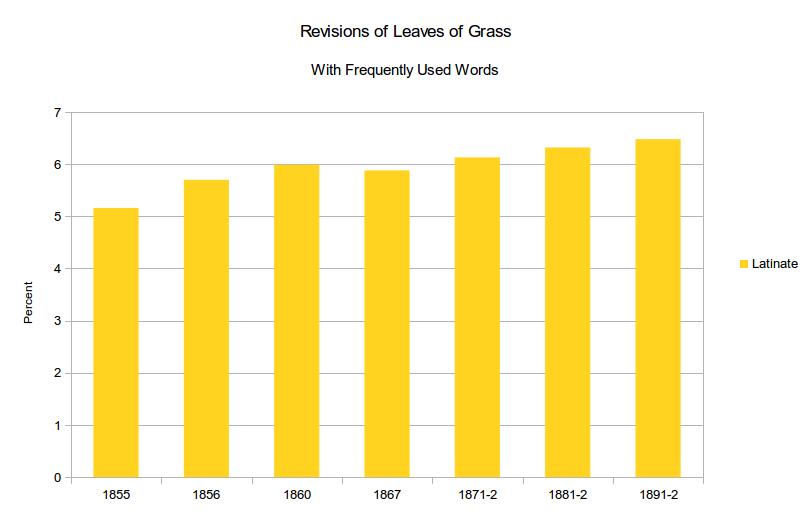

The goal of this experiment is to test the hypothesis that Whitman increasingly uses words of Latinate origin in his revisions of Leaves of Grass. Thankfully, seven of these revisions were available in TEI XML from the Whitman Archive, so this test was relatively easy. A few lines of code were added to the code to strip out XML tags, and each of these TEI files were run through the program.

The results of these test were as previously speculated—the proportion of Latinate words increases with each revision of Leaves of Grass, but with one minor exception—that of 1867. LeMaster and Kummings call this edition “the most chaotic of all six editions,” whose significance “lies in its intriguing raggedness, which is embedded in the social upheaval in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War” (365). Can the “images of a coherent union” and the “urgently accented democratic nationality” which they claim characterize this edition account for the slight drop in Latinate words, or slight increase in Germanic words? Do the six new poems of this edition contain an unusually high proportion of Germanic words? These are questions that demand further investigation.

Note

This post is an adapted and expanded excerpt from my 2013 Master’s thesis, “Macro-Etymological Textual Analysis: an Application of Langauge History to Literary Criticism.” The program described herein is the web app created for these experiments, the Macro-Etymological Analyzer. Read more about the program and related experiments in my introductory post, “Introducing the Macro-Etymological Analyzer.”

Works Cited

Asselineau, Roger. The Evolution of Walt Whitman. Iowa City: U Iowa P, 1999. Google Books. Web. 1 December 2013.

LeMaster, J.R. and Donald Kummings, eds. Walt Whitman: An Encylopedia New York: Routledge, 1998. Google Books. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

Warren, James Perrin. Walt Whitman’s Language Experiment. University Park: Penn State P, 1990. Print.