Posted 2013-05-10

Have you ever wanted to livetweet a book? I often want to. Yet there doesn’t seem to be a standard way of doing that. You could tweet, for instance, “Oh Captain Wentworth! When will you propose? #JaneAustenPersuasion” but the hashtag isn’t standardized, so some people might be tweeting under #Persuasion and others under #AustenPersuasion. Furthermore, the hashtag isn’t specific enough to make it clear which part of the book you’re tweeting about. If you browse other tweets marked #JaneAustenPersuasion, you might find comments about other parts of the book, which may contain spoilers.

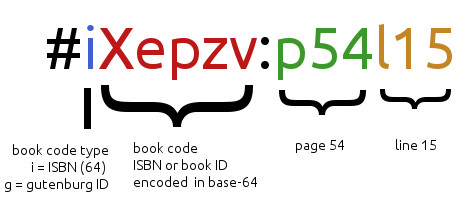

Enter Annotags, a concept for a literary annotation hashtag, or annotag. Whenever you want to tweet about part of a book, use this format:

The first letter is the book code type. Uppercase letters refer to raw codes and IDs, and lowercase letters refer to base 64-encoded codes. Here are some examples:

I= Raw ISBN, ex. I0393911535.i= Base 64-encoded ISBN, ex. iXepzvG= raw Project Gutenberg book ID, ex. G105.g= Base 64-encoded Gutenberg book ID, ex. gBpB= Google Books ID.O= Raw OCLC Number. Ex. O29877721. These can be found using Worldcat.o= Base 64-encoded OCLC number. Ex. oBx-XZ.

Any other sources can be added to this list. I’m working on a way to shorten DOIs, for instance.

The next letters and numbers before the colon are the book code,

optionally encoded in base 64. What is base 64, you ask? It’s

just a mathy way to take a long number and convert it to a short string

of numbers and both uppercase and lowercase letters. That way, you can

take an unwieldy ISBN—the ISBN for the Norton Critical Edition of Jane

Austen’s Persuasion, for instance, is 0393911535—and write it

as “Xepzv”. Both I0393911535 and iXepzv are valid annotags, but the latter saves

five characters, which you can use to write “LOL!!” or whatever your

heart desires. To try this out, grab an ISBN of a book from Amazon.com

or equivalent, remove all the hyphens and paste it into a converter like

the annotag calculator I wrote

here, which will convert it into Base 64. Some book IDs won’t

benefit much from encoding, of course. Many Project Gutenberg etexts IDs

are short anyway, so you might as well keep them as-is. The Project

Gutenberg ebook for Persuasion, for instance, is listed as

“EBook #105,” which can be represented as the annotag #G105. No calculator required.

Next, there is a colon, followed by the location code. The location

code is made up of chapter numbers, page numbers, or whatever you like.

If you want to get super-specific—say, if you’re annotating a particular

word or phrase—add a line number or word number. If your book doesn’t

have page numbers (if you’re reading an etext, for instance), you can

index your location any way you want—by chapter and paragraph number, or

even chapter, paragraph, and word. This is simple, intuitive, and

human-readable. If your book code is G105,

and you want to tweet about something that happens in Chapter XXIII, you

can tweet “Oh no you di’n’t, Captain Wentworth! #G105:c23”. Because the

annotag is only eight characters, you have another 130 or so for your

witty, insightful commentary.

List of Location Abbreviations:

d= part (“division”), ex. d2c5 is Part II, Chapter 5.b= book, ex. D3c7 is Book III, Chapter 7. For those books that are divided into “books.”c= chapter, ex. c34 or cXXXIV is Chapter 34.p= page, ex. p54 is page 54.a= act, ex. a1 is Act I. To be used for drama.s= scene, ex. a1s3 is Act I, Scene 3.P= paragraph or stanza, ex. c5P2 is the second paragraph of Chapter 5.l= line number, ex. p76l20 is page 76, line 20.w= word number, ex. p82l10w4 is the fourth word of the tenth line on page 82.

Examples:

Not to be, man. Not to be. Get over it. #Hamlet #G1524:a3s1P24

- The Gutenberg Ebook for Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, Act III, Scene 1, paragraph 24.

Septimus’s shell shock makes him unusually atune to nature. #Dalloway #iZOO:p22

- The Harcourt Annotated Edition of Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway, page 22.

What circles does the blackbird mark, exactly? #WallaceStevens #iB8F4h:p94P2

- The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” page 94, second stanza.

Advantages of Annotagging:

- It’s decentralized, so it’s not contingent on any one particular institution or website.

- Annotations are owned by their writers, not by the website that hosts them.

- Annotags are mostly human-readable. Once you know the code for your

book, it’s easy to figure out what “p54” means (hint: it’s page

54).

- Annotagging allows you to comment on both paper books and ebooks, and refer to specific editions when necessary.

- You don’t even need a computer to annotweet. Just send an SMS to your twitter account.

- No registration necessary, provided you already have an account on twitter or identi.ca.

- If you use Annotags in your blog posts, you aren’t restricted to the 140-character limit of microblogging platforms. You can even Annotag your scholarly papers.

Future Applications

There are lots of ways that apps could interface with this type of protocol. Here are some ideas:

- A webapp to generate Annotags, allowing the user to look up books by author, title, or ISBN, and generate Annotags from them.

- A webapp to aggregate Annotweets and display them in the margins of an etext, so that users can read an etext online and see what people have tweeted about it. Tweets that are line-specific will appear right next to those lines in the etext.

- A mobile webapp or native mobile app (i.e. an Android app) that can generate Annotags, and maybe even scan book barcodes using one’s smartphone camera.

- A script that can expand Annotags to regular MLA-compliant bibliographic entries.

- A browser extension (i.e. a Firefox plugin) that automatically generates Annotags for books when you visit a book page on Amazon or Worldcat.

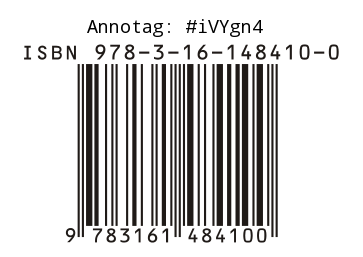

- Labels for paper books that include that book’s annotag, pre-calculated: